Life

Telling Our Kids To "Walk Up, Not Out" Isn't Just Wrong, It's Incredibly Dangerous

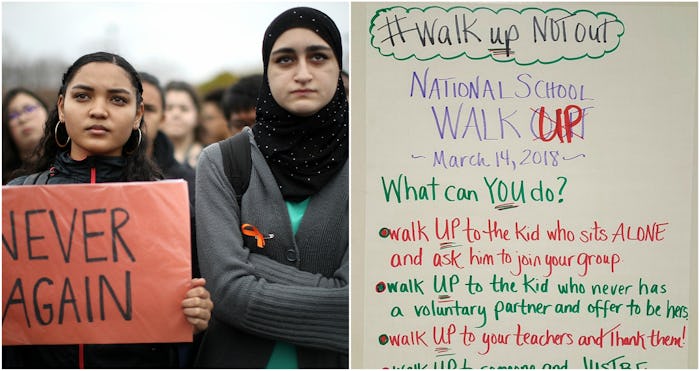

On March 14, students of all ages, races, and backgrounds walked out of their classrooms to protest ongoing, systemic gun violence that has claimed the lives of 7,000 students since 20 kindergarteners and six teachers were killed in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. While teachers, school districts, parents, and adults from across the country stood by the students, if not physically then in spirit, one middle school teacher offered an alternative. Jodie Katsetos, a sixth-grade teacher, encouraged her students to "walk up" instead of walk out. Since then her message has gone viral, as more and more people shared her image online via Twitter and Facebook. But "walking up" won't solve the problem. In fact, it might just put more students in danger.

Katsetos is a middle school teacher at Arcadia Middle School in Oak Hall, Virginia. Prior to the national walk out, she hung up a poster in her classroom encouraging her students to "walk up not out." Using the hashtag #WalkUpNotOut, Katsetos wrote "National School Walk Out" with the "Out" crossed out and "UP" written over it in red marker. Below was a list of "action items" students could take to "walk up," including: "walk UP to the kid who sits alone and ask him to join your group, walk UP to the kid who never has a voluntary partner and offer to be hers," and "walk UP to someone and just be nice."

Katsetpos's message is resonating across the internet, with her original Facebook post shared over 500,000 times and the hashtag being used on Twitter as a counter-protest to the national walk out.

But it isn't an either/or proposition. Walking out is a collective action designed to rally support and demonstrate a shared wish for gun control. "Walking up" is a nice idea that has the effect, here, of silencing and siphoning attention from an undeniable national gun crisis. Walking out is a powerful political statement being made by students too young to vote, but old enough to have performed multiple lockdown drills in their school. "Walking up" moves the public discourse offline and behind closed doors.

Should we, as adults and educators, be encouraging our children to be kind to one another? To be empathetic and inclusive and understanding of those who are different than they are? Absolutely. Nearly 30 percent of students age 12-18 reported being bullied on school grounds, according to the American Society for the Positive Care of Children (SPCC). Over 70 percent of young people say they've seen bullying in their schools, and 62 percent witnessed bullying two ore more times in the last month. Another 6 percent of students in grade 6-12 say they've experienced cyberbullying.

The effects of bullying are, of course, devastating. Students who experience bullying are at risk for poor school adjustment, sleep difficulties, anxiety, depression, mental-health and behavior problems, low self-esteem, strained relationships with friends and family, self-blame, and negative health effects such as headaches and stomachaches, according to The National Bullying Prevention Center.

Insinuating that children are responsible for mass gun violence because they simply don't take the time to 'befriend the lonely kid' is not only victim-blaming, it's dangerous.

But the "walk up not out" message fails to address what has made school shootings a now "normal" part of the United States education system: easy access to high-powered weapons. Furthermore, insinuating that children are responsible for mass gun violence because they simply don't take the time to "befriend the lonely kid" is not only victim-blaming, it's dangerous. We, as adults and educators, should not be encouraging our children to put themselves in potentially dangerous situations with a potentially volatile student for the betterment of everyone else. If a student is violent, they're violent.

This ill-advised message not-so-subtly hints at a theme that has remained prevalent in the wake of every mass school shooting, shifting the focus from common sense gun laws and readjusting the focal point to be, well, almost anything else. It's mental illness. It's autism. It's bullying. It's video games. It's the students' fault for not befriending the kid who made them uncomfortable and exhibited a few underlying red flags and seemed to be socially awkward to the point that people around them were afraid.

Law enforcement in Parkland, Florida, were contacted at least three times by people concerned the perpetrator could carry out a school shooting.

After the devastating shooting in Parkland, Florida, that took the lives of 17 innocent students and school staff, President Donald Trump tweeted: "So many signs that the Florida shooter was mentally disturbed, even expelled from school for bad and erratic behavior. Neighbors and classmates knew he was a big problem. Must always report instanced to authorities, again and again."

But the students did report instances again and again, according to student-turned-activist Emma Gonzalez during a gun control rally in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, just days after the Parkland Shooting. "We did, time and time again, "Gonzalez said. "Since he was in middle school ... it was no surprise to anyone who knew him to hear that he was the shooter. Those talking about how we should have not ostracized him, you didn't know this kid. OK? We did." Law enforcement in Parkland, Florida, were contacted at least three times by people concerned the perpetrator could carry out a school shooting, reports the Washington Post.

Suggesting to our children that they are somehow failing their classmates, teachers, school staff, and parents, by not befriending someone who makes them uncomfortable, is a form of victim-blaming. Insinuating that if the school shooters at Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, Virginia Tech, Benton, or Marshal Country, or the shooters responsible for the mass killings in Las Vegas, Orlando, and San Bernadino had only been popular or had friends, they wouldn't have used weapons of war to kill an unfathomable amount of innocent lives, is like telling a rape victim if his or her rapist had a girlfriend their sexual assault never would have happened.

We'd rather tell our children — our children — to do more than tell our elected officials to pass common sense gun laws.

The 19-year-old Parkland shooter was abusive towards his ex-girlfriend, was expelled for getting in a fight with her new boyfriend, and harassed another female student "to the point of stalking her," according to The New York Times. Another student said he cut ties with the shooter after he started "going after" and "threatening" a female friend. Should we be telling students this person is someone they should continue to befriend? Is this person — who stalks, harasses, abuses, and fights other students — someone you would feel comfortable having your child spend time with? Most importantly, is this someone who should be able to purchase a semi-automatic weapon?

In the state of Florida, an 18-year-old can legally purchase a firearm, and there is no state requirement for a gun owner to own a permit for a shotgun or rifle. In Florida it's easier to buy an AR-15 than it is to buy a handgun. In fact, in most states, you can buy an AR-15 military-style weapon before you can legally buy a beer. The ease in which a disturbed, lonely, depressed, violent, potentially homicidal young person can buy a gun is undoubtedly a problem contributing to school shootings, yet it is the one problem we, as a culture, are continuing to side-step. We'd rather tell our children — our children — to do more than tell our elected officials to pass common sense gun laws.

So while our kids are busy walking out of their schools as a direct result of our inaction and inability to pass common sense gun laws that would make them safe in school, perhaps it's our turn, as adults, to walk up.

Walk up to your local representative and demand legislative action. Walk up to your local #MarchForOurLives location on March 24 and stand shoulder-to-shoulder with students. Walk up to your bank and, if you can, donate to Everytown for Gun Safety, the Brady Campaign, the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, or the Giffords Law Center.

Walk up to the mirror, look yourself in the eyes, and tell yourself that you've done everything you can to prevent the next mass shooting. And if you can't, stop looking to the students to save themselves and start looking at yourself.

Check out Romper's new video series, Bearing The Motherload, where disagreeing parents from different sides of an issue sit down with a mediator and talk about how to support (and not judge) each other’s parenting perspectives. New episodes air Mondays on Facebook.