Life

The Book That Helped Me Survive Being Abandoned By The Person Who Brought Me To Life

Reading a book 200 times is a surefire way to find out whether you love it or want to throw its rhyming llama couplets into the diaper pail. Children's books especially do a tricky dance for an audience of squinty-eyed parents and wide-eyed tots: the best ones, like a syringe of infant-suspension Tylenol, have a little something for the parent at the end. These are the ones we are celebrating in This Book Belongs To — the books that send us back to the days of our own footed pajamas, and make us feel only half-exhausted when our tiny overlords ask to read them one more time.

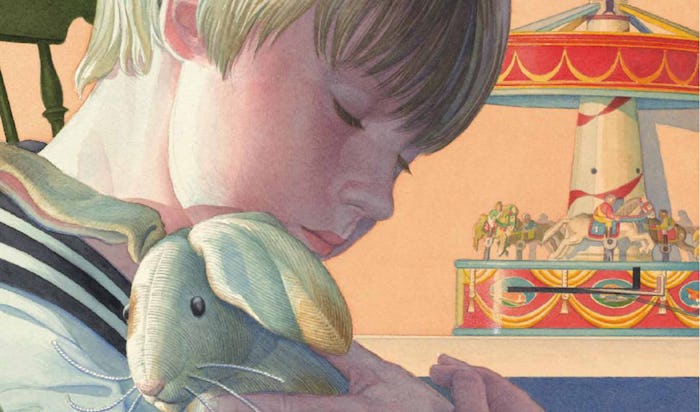

When I was a child, I lived in fear that someone would throw away my teddy bear, Chips. I’d read The Velveteen Rabbit so many times that I was convinced it was inevitable. But I would never let it happen. I would never let my beloved teddy bear cry in a rubbish heap, convinced I had abandoned him. He, like the titular rabbit, was Real, and deserved to be treated as such. Real didn’t have to mean the pain of abandonment, no matter what the Skin Horse said in the book.

So I managed to protect and hang onto that ragged, ripped, threadbear teddy bear until I was 29. At that age, seven years ago, Chips lived on a shelf in my room, hardly cuddled, gathering dust. And then I met Mya. Mya wasn’t her name, then, and “she” wasn’t her pronoun. Alex wasn’t my name, then, and “they” wasn’t my pronoun. The first time Mya slept in my apartment, she discovered Chips.

“Why is he all alone on a shelf?” she asked. I recognized immediately in her the empathy for the inanimate that lived in me, that made me feel sad when items went unused, that made me a writer and a novelist, able to care about imaginary lives for years at a time. From then on, Chips slept in my bed with us. When Mya had surgery on her vocal chords, I bought her a teddy bear named Little Bear. For years, we had entire conversations through the mouths of Chips and Little Bear.

We loved each other so much. We loved each other enough to give each other the space to recognize ourselves. We began exploring our gender identities. We supported each other in it, even when our families and friends didn’t. This is what it felt like to be loved, I marveled as I started wearing new clothes, got the haircut I’d always wanted, changed my name and pronouns. This is what it felt like to become Real.

I should have remembered what the Skin Horse said. One should always remember what the Skin Horse said.

"’Does it hurt?’ asked the Rabbit.

‘Sometimes,’ said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. "When you are Real you don't mind being hurt.’”

It was spring, and we’d been married for almost two years when Mya went to San Francisco to look at apartments for us. When she sent me videos of her walking down tree-lined streets and telling me she loved me. When she met the person she would leave me for, a few weeks later.

Maybe this is what the Skin Horse meant: that once you become really Real, you always have this memory of hurt in your heart, and you’re never caught unawares by it again.

The time that followed was one of the worst in my life. All I could think of was The Velveteen Rabbit, how the rabbit had thought he and The Boy he loved so were going to the seashore after The Boy’s long illness, and instead he ended up in a rubbish heap, waiting to be burned with all the other toys.

“Of what use was it to be loved and lose one's beauty and become Real if it all ended like this?”

There was no nursery magic, there was no fairy to come along and show it to me, I was sure, not in real life. In real life there was just the pain of the end of love, and the knowledge that even the act of becoming Real meant nothing. There was just the rabbit, waiting with the other toys, to be burned.

I lived in this pain for nearly three years. And then, all at once, like bursting into the light when you didn’t know the tunnel had an end, it was over. Time and the ability to heal had been the magic from the fairy wand. The sadness and the hurt were gone. And I was still Real, my true self, who I was always meant to be.

Suddenly I understood that scene at the end of the book where the rabbit — a real, live, jumping rabbit — sees The Boy and they look at each other. I can never go back to the love or the person that made me real, just like the rabbit couldn’t; that’s not how it works. But, sometimes, when the hurt is at bay, I can look back tenderly at the person who caused both the worst hurt and the greatest joy in my life. I can see that neither could exist without the other.

I’m not sure I’ll ever love someone that way in my life again, with a trust that hurt will never come and love will be forever. But maybe this is what the Skin Horse meant: that once you become really Real, you always have this memory of hurt in your heart, and you’re never caught unawares by it again.

Today, my teddy bear, Chips, lives on a shelf in my bedroom. There’s still a scarf tied around his neck that my ex-wife put there one day, long ago.

The Velveteen Rabbit: Or How Toys Become Real by Margery Williams, $3, Amazon