Parenting

Motherhood Will Not Be Optimized

I am not an ideal mother. I don’t want to be. I want to be human.

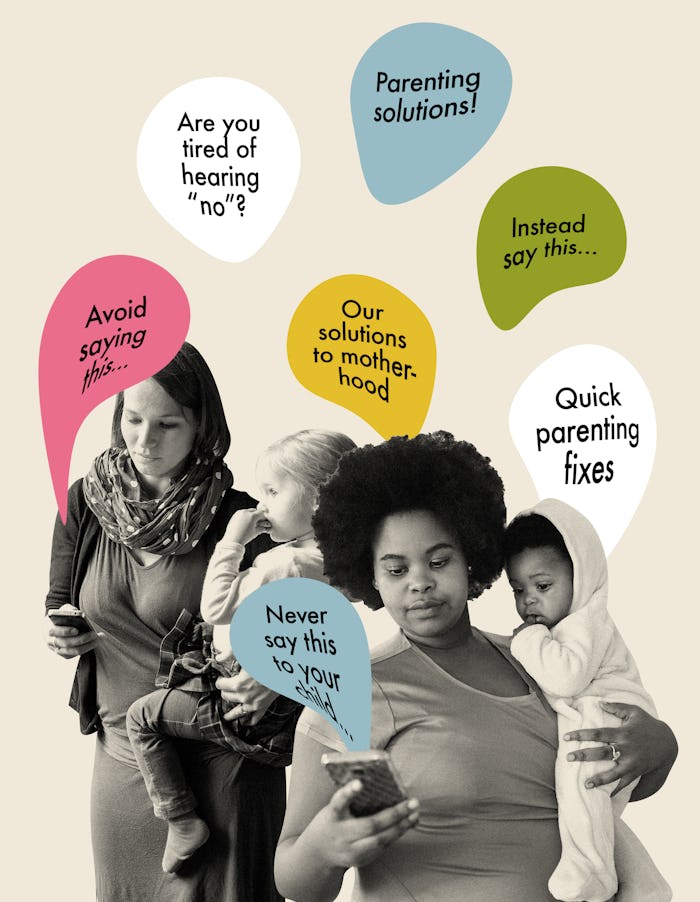

This is how it usually happens: My Instagram stories flip from a photo of someone’s ficus plant to someone’s cute toddler to an infographic that I press my thumb on the screen to read. The font is designed to be if not stylish, at least non-offensive. Its background color is a muted millennial pink or maybe a pistachio green or the pale yellow of a Starburst. Posts like these seemed to have really proliferated during the pandemic, with so many of us stuck at home. Or maybe it’s that I’ve been online too much, in need of connection and a way to comprehend what’s happening. The advice on these posts is straightforward and accessible, and it’s meant for a mother. For me, I suppose. One of these memes might list phrases to say to your child when they’re having a temper tantrum. Another might bisect a page between “DOs” and “DON’Ts” for when your child is, say, eating sand or throwing food at you or sobbing over a cut banana. They seem to suggest that parenting, and changing your parenting, is, like the memes themselves, simple and straightforward.

At first glance, you might expect me to be the ideal audience for this niche internet content. After all, I have three young kids: a 5-year-old daughter and two sons, one nearly 10, the other nearly 2. My own Instagram account is filled with dozens of photos of them hugging and mugging for the camera, showing off their art and games, and reading books on their own like good little fantasy children.

I myself was an A student in school; I got married in my mid-20s; I had my first child at 30. Even at the height of the pandemic, I wrote regularly and kept up with email. I wore pants with buttons and zippers. I shaved my legs nightly and put myself to bed at a respectable hour. For years, I’ve exercised at least four times a week. (I swear I’m not as uptight as it sounds; I simply find solace in being efficient and productive.) You would think that my personality and life trajectory would mean I’m predisposed to enjoying accessible instructions on effective parenting.

Motherhood is wonderfully (and frustratingly) outside-the-lines and inefficient. It contradicts the very messages these parenting memes espouse, which is that parenting is something to be solved.

My experience with motherhood, however, is in direct tension with the so-called uptight parts of my personality. My kids don’t care about my personal self-care practices or my ambition, and there are no grades or medals for being an excellent mom — there’s certainly no salary or year-end bonus, either. My children are not expressions of my efficient, productive habits and lifestyle; if anything, they’re in opposition to it. But this brand of parenthood content, easily digestible and infinitely shareable, tells me otherwise. It wants me to believe that motherhood can and should be folded into a neat lifestyle of ease and achievement. Under the guise of being helpful, these posts set yet another impossible standard for mothers.

Thankfully, having kids has helped me see the futility of this striving because motherhood is wonderfully (and frustratingly) outside-the-lines and inefficient. It contradicts the very messages these parenting memes espouse, which is that parenting is something to be solved. These memes imply that you can improve your parenting easily... and that parenting is something to be improved at all.

In her essay “Always Be Optimizing,” Jia Tolentino explores the phenomenon of the ideal woman who’s always improving herself, from her fitness plan to her skin care regimen. This constantly optimizing woman “wrings as much value out of her particular position as she can,” and under this system, she strives for a life that’s seamless, which leaves no room for mess or vulnerability.

But when I see these Instagram parenting memes, I think, I’ve caught myself optimizing almost everything in my life. There’s no way I’m optimizing motherhood.

Of course, this version of life is mythic and forever unattainable. Tolentino writes, “Figuring out how to get better at being a woman is a ridiculous and often amoral project of learning how to get better at life under accelerated capitalism.” Since I am the sort of woman who is willing to get up before dawn to do a barre-based workout, I can relate to the project of self-improvement, both its absurdity and my attachment to it. But when I see these Instagram parenting memes, I think, I’ve caught myself optimizing almost everything in my life. There’s no way I’m optimizing motherhood.

Could I even do it if I wanted to? I can’t help thinking about how many times the sort of “easy” parenting advice proffered in an Instagram post hasn’t worked for me, particularly with my oldest son, who’s always been challenging.

Almost two years ago, at age 8, he was finally, after a billion calls from teachers and principals, diagnosed with a neurological discrepancy disorder. This means he didn’t exactly qualify for any of the other diagnoses, like ADHD, but his behavior can read like that. It means he is “twice exceptional” — exceptionally smart and exceptionally bad at life skills… like holding a fork. It means that although there are ways to help him, like visits to the occupational therapist, this is who he is and how his brain works.

It also means that he’s Instagram-meme-proof. He never stops moving, and he doesn’t listen. He doesn’t sit properly at meals. He’s turned disagreeing into a sport and his tantrums last longer than a sleep-deprived toddler’s. Sometimes he writhes around on the living room floor like a live wire, a surplus of energy coursing through him, and I feel powerless to help him.

If parenting has taught me anything, it’s humility and surrender. Raising children defies the neatness and simplification of an internet meme.

When you follow Instagram advice and it works, you feel a streak of accomplishment. You’re victorious because a minor tweak showed results. As if parenting were a test you could study for and ace. Under this rubric, parenting becomes another thing to do, like drinking more water or doing ab crunches or getting to inbox zero or adding collagen to your morning coffee. Your children are an extension of you. And if you can always be improved, then so can your kids and your relationship with them, right?

But when the advice doesn’t work? You feel bad. You took the test, and you failed.

I failed the test so many times before I finally just stopped taking the test.

I’m grateful for that failure though, and that my son defied every quick parenting lesson, because it made me nearly immune to that seductive messaging. Even though my second and third children are neurotypical, I believe they, too, are Instagram-meme-proof because parenting is never easy, no matter who your child is. The stakes are just too high, and a quick script change won’t bring about profound and lasting change. Nothing short of intensive therapy can truly alter how you approach caregiving. While this may make some parents feel helpless, for me it’s liberating.

If parenting has taught me anything, it’s humility and surrender. Raising children defies the neatness and simplification of an internet meme. Parenting is mucus and sh*t and tears. It’s a scary-deep well of love and the persistent fear that the person you love most will die. It’s physical and emotional intimacy. It’s exhaustion and mind-melting conversations. Like anything meaningful, it can’t be contained to a slick grid or a pithy post. Why would we want it to be?

Either way, over a year and a half of pandemic parenting has rendered these posts even more upsetting for me. We don’t need cards with “the right words” for a kid’s meltdown. We need economic security and a safe place for our children to grow up and a government that cares about our health and livelihood. We need a community in which to raise our children. What we don’t need are snappy mothering tips. Our individual actions matter, but they’re not the change required to truly help mothers in 2021.

My kids, at least, with the beauty and brutality of their constant presence, remind me daily that they cannot and should not be made better. They just are.

Lately, I’ve been questioning my desires for seamlessness and efficiency, and I’m trying to unyoke these desires from my ideas of success, victory, and even ethics. I am not a better person because I read a certain number of books a year or exfoliate regularly. I want to enjoy things for the sake of enjoying them, and if I experience a surge of accomplishment as I check activities off my always-running mental to-do list, I acknowledge it, shrug it off, and move on. My kids, at least, with the beauty and brutality of their constant presence, remind me daily that they cannot and should not be made better. They just are.

Over a single weekend, I dealt with one child obsessively cleaning up toys (even while another sibling was mid-play), and one yelling at me, “I’ll murder you and drink your blood afterward,” and another crying mournfully for breastmilk that I wouldn’t give him. When the weaning baby refused to look at me, it was a stab to my heart. To my soul, really. The kid who was neurotically tidying up and the one who was screaming that he was going to murder me had once nursed, too. They’d all been my babies. Meanwhile, inside my bra, my nipples sagged, cock-eyed and rough as beef jerky. Put that in your Instagram stories.

I’m sure I didn’t handle any of these challenges in the most productive or efficient way. I yelled. I probably said, “I f*cking hate this.” I definitely said, “Oh stop, you’re fine.”

I am not an ideal mother. I don’t want to be. I want to be human.

That same weekend, there were moments of pure joy: laughing and cuddling and witnessing human development in all its wacked-out magnificence. For a while there, I slipped out of the optimization noose. To believe I could improve as a mother misunderstands the wild and stunning messiness of my children and my relationship to them.