pride

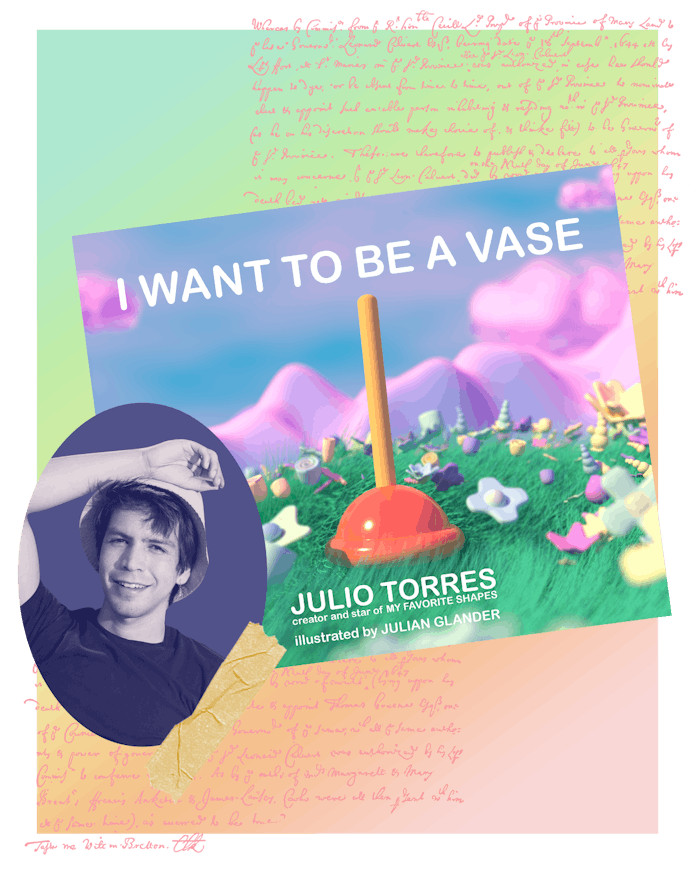

Julio Torres’ I Want To Be A Vase Is Delightfully Strange & Oddly Touching

“Ideally, a kid will pick this up and they’ll feel like they’re getting away with something.”

In the opening pages of I Want to Be a Vase, the debut picture book from comedian Julio Torres, a plunger makes an announcement: It wants to be a vase. Surprised at first, its fellow household objects quickly respond with revelations of their own. Enter the pot who wants to be a trash can, the trash can who wants to be a throw pillow, and the blow-dryer who’d really rather be a vacuum. Delightfully strange and oddly touching, I Want to Be a Vase is the newest entry into the canon of very good children’s books by comedic multihyphenates.

“I had an acute awareness of the differences between me and other kids from a very early age,” says Torres, reflecting on how his childhood in El Salvador shaped his approach to the story. After relocating to the States for college, he spent years cultivating a following as one of Brooklyn’s most proudly niche comics before finding his way to Saturday Night Live in 2016. During his fairly brief tenure at the show — he left in 2019 to co-create Los Espookys, a Spanish-language HBO show about a horror-loving group of misfits, with Ana Fabrega and Fred Armisen — he wrote an astonishing number of iconic SNL sketches. See “Wells for Boys,” a mock Fisher-Price ad spot that offers “wells for sensitive boys to wish upon, confide in, and reflect by.” In hindsight, the sketch was a turning point, as rarely if ever in the show’s history had queerness been so empathically (and hilariously) brought to the fore.

Likewise, I Want to Be a Vase, with its array of pinkish hues and themes of self-expression and acceptance, feels like an obvious allegory for queer identity. But Torres explains that he was also thinking about class, nationality, and various other ways in which kids might feel limited by forces outside of their control. Ahead of the book’s release, we chatted with Torres about how he approached writing for a younger audience, why the book can be read multiple ways, and what he hopes kids and their parents will take away from the story.

Ideally, a kid will pick this up — or their parents will pick this up for them — and they’ll feel like they’re getting away with something.

What was most exciting to you about writing a picture book?

I knew that I wanted to write about moments when I felt limited by norms that I don’t agree with, and I felt like that message would be particularly important if geared toward a younger audience. I was also already tapping into so much of my own childhood in creating work for people my age, and it was exciting to be like, “What if I had heard these things when I was a kid?”

Ideally, a kid will pick this up — or their parents will pick this up for them — and they’ll feel like they’re getting away with something.

How did you find writing for children’s books to be different from writing for TV?

When you’re writing for kids, you have to make sure that everything is really clear. My editor was very helpful in keeping me on the kids track by being like, “These words are too big,” or “There’s too much text here.” In many ways, though, it didn’t feel a whole lot different. It felt very compatible with my work in terms of the sense of imagination and ideas that I was playing with, and that’s why I hope that kids don’t feel like the book is talking down to them.

The other thing is, you have to be very attuned to the moral lessons in the work. Kids can enjoy things just because they enjoy them, obviously, but I think it’s important to think about the messages they’re receiving at such a young age.

Is there children’s entertainment that you think really misses the mark in terms of messaging?

My biggest observation about work for kids is that there’s this obsession with the individual. It’s like, “You are different, you are special, and you will work harder and be better than everyone else.” That way of thinking is so deeply intertwined with the idea of the American Dream, and it feels like something that we should be questioning.

By always pushing kids to pursue self-gain, we’re not really encouraging them to think about themselves as part of a community. We want kids to seek out whatever’s best for themselves, but it’s also important for them to look around and see who else might need help.

How did the book’s visual world come together?

My first question for the book was, can it be photographs? I really didn’t like the overly tender quality of a lot of children’s illustrations, which to me feel like you’d see in a nursery or something. It was important to me that kids didn’t feel cradled by the book, and I discovered through working with Julian [Glander] this cinematic quality that I really loved. I wanted everything to feel like you could touch it, almost like pictures of plastic models, so that was just a really good match.

I’ve always felt like I exist outside of the limitations of a world that was created by other people.

How did your experience of growing up queer shape how you approach your work?

I always felt like an exception to everything. I always felt like, There are rules and expectations for other people, but I’m over here. And as long as I’m over here quietly, I’ll be OK. Queerness was a big part of that, but there was also a moral and religious aspect. Even as a kid, I very clearly did not believe in God, but I was very quiet about that. I knew I wasn’t supposed to bring too much attention to it. I went to a private school, and I was there via scholarship, so there was also a class issue that set me apart from others.

When I came to the States, there were obvious hurdles for me that other people didn’t have to deal with, and I guess in a way that took the place of queerness in terms of me feeling othered. I’ve always felt like I exist outside of the limitations of a world that was created by other people. As painful as that feeling was when I was a kid, as an adult it has encouraged me to embrace the things that I do differently. It really has freed me from some of the limitations and expectations that others either thrive within or are bound to, depending on how you look at it.

This is a really scary time for a lot of people, particularly queer parents and parents of queer kids. What do you hope people take away from reading your book?

Every kid should be told that it’s OK to be who they are and who they want to be. I hope by entering this world, kids will be encouraged to really go through that journey of self-discovery. Obviously, this book really lends itself to be read in terms of queerness, but I was also thinking about this in terms of class and social mobility. There are so many different ways that kids are limited by things that they have no control over.

Lastly, if you could be like Plunger and pick any other job, which would you choose?

I would definitely be a designer of some sort. Maybe a set designer. My mom was an architect, so she’s obviously very visual, and the way that things looked always mattered deeply to us. As an adult, it still brings me a lot of joy. Right now, for example, I have to find a new apartment, and it’s not ideal timing to have to do that. But then I’m like, “Ooh, but now I get to decorate a whole new apartment.” I love a project. I love creating new worlds and to do that visually is just very exciting to me.

Julio Torres’ new children’s book I Want To Be A Vase is available now.

This article was originally published on