Must Reads

On Keeping Black Kids Safe While Encouraging Them To Be Audaciously Joyful

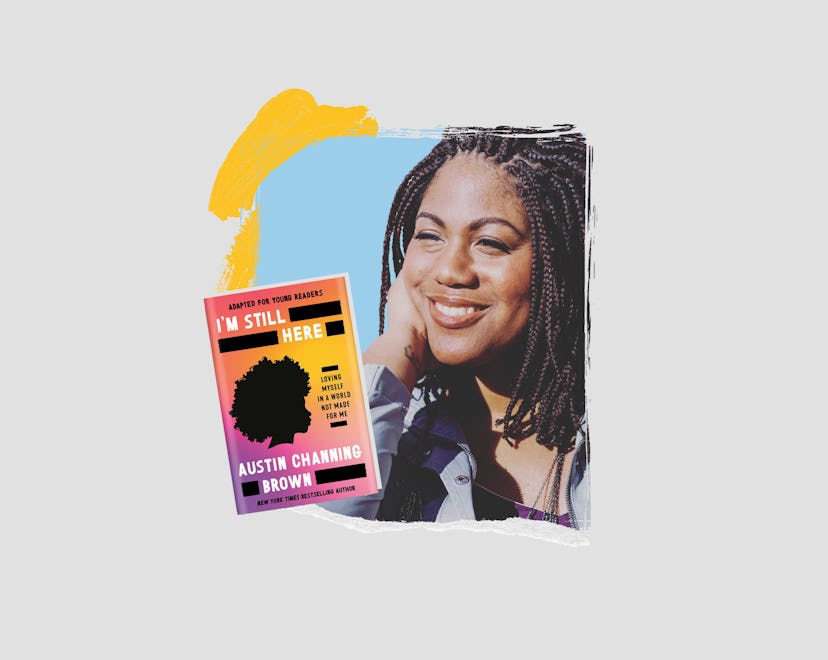

Racial justice advocate and best-selling author Austin Channing Brown on raising kids, centering joy, and not being afraid to mess up.

“Nobody in here is superior to anybody else, which means we are all going to mess up,” Austin Channing Brown, New York Times bestselling author and racial justice activist, told a crowded Scottsdale ballroom filled with women earlier this month. “The beautiful thing is that we also get to reconcile,” she continued. “And we get to learn, and we get to heal, and we get to chart a new way forward because we have learned something about ourselves — and that is what makes racial justice so invigorating.”

I had the pleasure of joining Brown, author of I’m Still Here: Black Dignity In A World Made For Whiteness, on stage at the 2023 Mom 2.0 Summit for an incredibly moving conversation focused on the connection between racial justice, parenting, and joy. A throughline of our conversation was the importance of elevating our joy, specifically as it pertains to antiracism work and the work we do fighting for a liberated world for our children.

Austin’s new book, a young readers adaptation of her viral memoir, takes all the gems from her original publication and brings it to our kids in a way that makes it seem like Brown and her reader are just two friends chatting at the ice-cream parlor. In the book, she reminisces about her youth, lessons her parents taught her, and how she became a powerful activist who is shifting perspectives the country over.

In our chat as one of the keynote events at the Summit (an annual gathering of parenting influencers and leaders who create content online and on-air about parenting, politics, business, social change, travel, and more), Brown shared how to keep our Black kids safe while helping them be audaciously joyful, especially in public. She also left us with some much-needed advice for how us mamas can find and hold precious joy in the midst of the jointly messy work of motherhood and racial justice.

I can’t tell you how to do it and never make a mistake. But hello somebody! We’re moms. We know how to make mistakes and keep going. We know how to fix, how to tweak something that isn’t working. We know how to ask new questions. We know how to stop the whole room and go a different direction — and that is what the work of racial justice is.

Below is a condensed version of our conversation, which left me inspired and invigorated — and a .

Tabitha St. Bernard-Jacobs: Can you talk a little bit about how mentors throughout your life have really helped you reaffirm yourself and find your voice and elevate your joy?

Austin Channing Brown: So I’ve spent a good deal of time in predominantly white spaces and they’re tricky… And what I have found as I’ve been navigating those spaces throughout my entire life is that they don’t have to suck. They can, but they don’t have to. One of the stories that I talk about in the book is being in elementary school where our music teacher pulled the three Black girls in our class out of our regular classroom in order to just give us the space to sing. Now friends, we could not actually sing. This is a very important note. There were no concerts. We did not perform anywhere. This was just an opportunity for us to be together. A lot of times what happens is people get offended when people of color, and Black women in particular, just want to be together — as opposed to seeing it as fertile ground for us to be who we are. And that is so important and it made all the difference.

TSBJ: You talk about racial justice work as being risky and messy. It’s not simple or straightforward. Being a mom is also messy. How can we find a path to racial justice through the messiness of being moms?

ACB: On a daily basis, [moms] deal with the hardest things in the world … and then we have to explain that world. This is what moms do. And racial justice is not like rocket science. It’s messy and it’s risky. I can’t tell you how to do it without getting in trouble. I can’t tell you how to do it and still have everybody like you. I can’t tell you how to do it and never make a mistake. But hello somebody! We’re moms. Aren’t we used to doing all the above? We know how to make mistakes and keep going. We know how to fix, how to tweak something that isn’t working. We know how to ask new questions. We know how to stop the whole room and go a different direction — and that is what the work of racial justice is. It is being in a room where you see something happening; where someone is not being treated equally and saying, “I’m about to shut this whole room down.” So many of us have learned how to do these things in other areas of our life. And all I’m asking is that you bring it over to racial justice too.

The truth is the number one question I get from white women who want to participate in racial justice really is how do I do this without ever causing harm or hurt or doing anything incorrectly? And I’m going to tell all of you: you’ve already messed up. You have already said something inappropriate. You have already offended somebody. Like, it’s already happened. And yet here you still are. You’re still here. And so you don’t have to shrink. You don’t have to shrivel up because you made a mistake. What would you tell your children when they make a mistake? Do you want them to just go run and hide? Right? So we have to model the same thing that we’re saying that we want for our children and our communities.

So when you make a mistake: “Damn, I’m sorry. I sure didn’t mean to do that and I promise I’m not ever going to do it again,” and move on. There’s not one Black woman or woman of color who expects you to be perfect. It’s not real. That’s not realistic. I am still learning. I am still growing. I am still reading. I am still changing my language. I am still figuring things out. This is a journey for all of us, and perfection, I am convinced, is an outgrowth of white supremacy.

TSBJ: You talk about being taught by your parents that the way to be Black as a young child was to be inconspicuous. And that was done not because our parents didn’t want us to take up space, but because they wanted us to be safe. How are you raising your son to be audaciously joyful and bold, but still keeping him safe at the same time?

ACB: The truth is, I still follow a lot of the same rules that my parents gave me. So there will come a day when I will teach my son that he cannot wear his hood or his hat into a store. That day is coming. I will teach him what he needs to do when he gets pulled over by the police and we will have a whole conversation about how his pride and his ego has to be rooted in getting his butt back home, not in responding to the situation. There are a lot of things that I will have to teach my beautiful little boy that I don’t want to, but I have to.

To be able to say, “I know what the world thinks about you, but girl, let me tell you what I see.”

But also, there is joy. There is joy when I buy my husband and my father-in-law tickets to go see their first NBA basketball game together. There is also an appreciation of his culture, an appreciation of the way we talk at home, an appreciation of the music, an appreciation of the icons, and now all of that runs through his blood and he will find his own way. But there is no doubt that there are things that we will have to teach him about how to be a Black boy in white America.

TSBJ: Your book was recently adapted for young readers. Do you have any advice for how we can support our kids to really understand some of these big concepts and issues in the book?

ACB: My racial awakening really started when I was 8 years old. So I think 8 would be the youngest I would suggest. But also, even though this book is chronological, the chapters aren’t built on one another. So you as a parent can read through the whole book and then decide which chapters your child is ready for based on the conversations that you’re having and their school system.

TSBJ: I’m going to try to summarize some of the lessons from your book for us Black adults. Some of them are:

- No shrinking.

- Make your life more than about The Struggle.

- Pursue both justice and joy.

- Don’t experience community hurt and then deny yourself community hope.

- Don’t be ashamed to need Black love.

ACB: Can we end talking about Black love? Oh, my goodness. The love is so deep. When you think about the fact that for centuries — and currently — we have been told that we are inferior. And more than that, told that we’re animalistic, told that we have no culture, told that we are not even humans. To be able to see one another... To be able to be like, “Girl, I see you. Oh, oh, you cute today, huh?” To be able to express Black love. To be able to say, “I know what the world thinks about you, but girl, let me tell you what I see.” Do not deny yourself Black love. And those of you who have friends or family members who are Black, I know you’ve experienced Black love before because it comes out of our pores. The world would be so much better if it recognized the hopefulness and the revolution that is Black love.

Austin Channing Brown’s books are available everywhere books are sold including your local Black-owned bookstore. You can also snag her books at your local library. Romper was a proud media partner of the 2023 Mom 2.0 Summit.

Raising Anti-Racist Kids is a column written by Tabitha St. Bernard-Jacobs focused on education and actionable steps for parents who are committed to raising anti-racist children and cultivating homes rooted in liberation for Black people. To reach Tabitha, email hello@romper.com or follow her on Instagram.