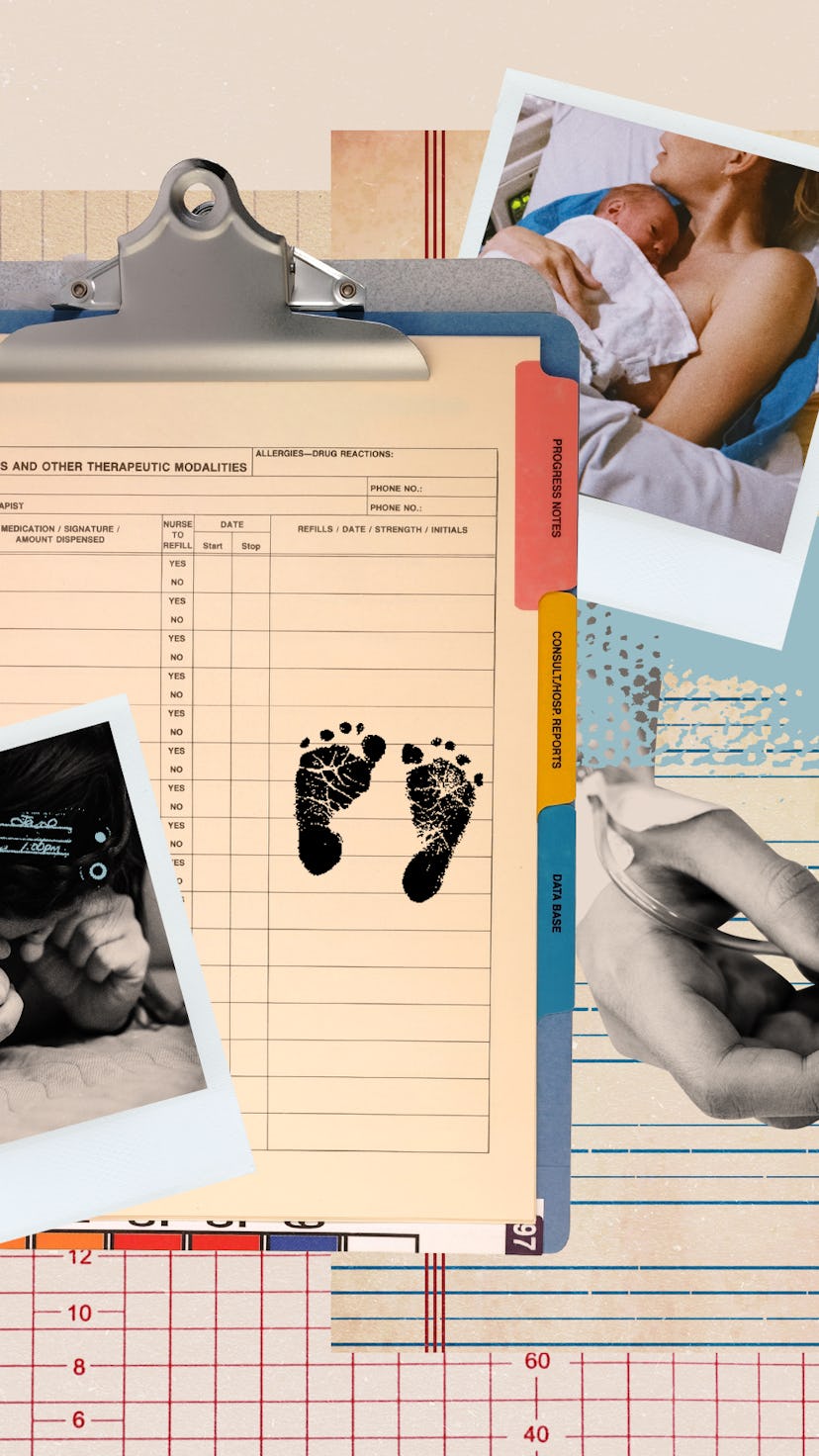

Birth Stories

Reading My Hospital Records Changed How I Thought About My Traumatic Birth

Studies indicate 25-34% of postpartum parents report a traumatic birth. This past August, after my second child was born, I became one of them.

Birth memories make up their own genre of recollection. For the person giving birth, they can be very weird indeed: extraordinarily intense hours turn into a fog; a few snapshot-like moments play on repeat in your mind’s eye. Studies indicate 25-34% of postpartum parents report a traumatic birth. This past August, after my second child was born, I became one of them.

In those early hours and days in the hospital, I smiled so much my face hurt. And I was overjoyed and cognizant of my good fortune, but also flattened: a trope of parenthood that landed sooner than expected. A question echoed around my head on a loop: What had just happened? My disorientation and dissociation felt unfair to my brand-new child, whose dark, unblinking eyes seemed to stare right through me.

I hadn’t reckoned with feeling this way: When I thought back on my first child’s birth two years previously, in the same hospital with many of the same worries and hiccups during labor, the memory was dependably exhilarating. My second kid surely deserved a “good” birth story too — but even months later, I couldn’t think about it without spiraling into a dark, furious funk.

A question echoed around my head on a loop: What had just happened?

I must have done something wrong: I shouldn’t have labored at home so long. Or rather, I should have gone longer, free-birthed the baby accidentally-on-purpose in the bathroom. This haze of self-blame and extreme rewriting wasn’t doing me any good, and it refused to lift, despite a steadily growing bond with the baby herself. Clearly, I needed a way to reframe her arrival.

When I mentioned my rage to an experienced doula (now midwife), Lisa Gendron, I was surprised by her response. I could request my hospital records, and she could talk me through them. Initially this seemed redundant: it wasn’t like I planned to seek legal action (which, according to the Birth Trauma Association, is the most common motive for patients requesting their hospital records after birth). But as I stewed for a while longer over how difficult it was to handle my no-longer-fresh birth flashbacks, I became eager to read the hospital’s version of events — anything to cast a new perspective on that night.

The charge from the records office was $135; dismaying, since many of the 300+ pages I received were duplicates. They included the Emergency Department documentation (triage), Delivery record (including a multi-paragraph narrative), Obstetrics Progress (recovery) notes, lactation consult notes, a table of drugs and ointments given, pre-discharge evaluations, and many other pages of metrics and abbreviations I had to Google, plus the labs and notes from my prenatal appointments.

I learned something journalists and detectives know well: never rely fully on a single witness. Oddly, on the heart-thumping morning spent reading them, the most powerful sense I had was, This really happened. The events were fed back to me in small, mostly impersonal bites. As I read through the hospital’s version of how I had gone from dilated to stitched up, and my baby from fetus to child, I already felt less alone with those memories. Fear and trauma can add a layer of resistance to first-person narration. Similar to sexual assault, it can be tough to piece together a series of micro-events and identify where things veered from unfamiliar to not-OK. If the newborn is healthy, there is added pressure to retell the story in a wholly positive light. Paging through these records had a validating and neutralizing effect, well worth the price of a new pair of jeans.

One of the many bewildering aspects of my experience was that I’d liked and trusted everyone at the hospital. I just hadn’t understood the system in which they were trying to work. As Lisa talked me through the records, she explained the challenges of charting the fetal heart rate and what concerns may have driven the medical team attending me. Taking time to absorb the records helped, and discussing them with an informed professional helped even more.

Still, I had questions.

As I read through the hospital’s version of how I had gone from dilated to stitched up, and my baby from fetus to child, I already felt less alone with those memories.

In between the lines about tests run, medications given, and procedures done, there was a surprising amount of subjective commentary. In the notes on my initial assessment, my “Affect/Behavior” was “Appropriate, Calm, Cooperative.” In the brief narrative titled “Physical Exam,” the most turbulent quarter-hour of my life was summed up in a few lines, concluding, “Patient tolerated this process well.” (Not how I remember it.) I reported my contraction pain to be a 7, a lowball figure given in a mistimed attempt to impress my husband and doctors. Afterward, my Madonna-and-child pose apparently paid off: “Attachment Behaviors Observed.”

I got hung up on the qualitative notes, which struck me as jarring and bias-prone. How had those cheery initial assessments come to be, given that I was late in labor and being loud about it? And afterward, why did the fact that I cradled and fed the baby count for so much, when my psychic state was so crappy? Wasn’t it obvious I was performing the Good Patient and Nurturing Mother — putting up a front and inviting them to see through it, like when a grieving person says they are fine? Why was no one calling me on this? Out of all the vital signs and verbal exchanges reported in the records, these sections seemed set up for practitioners to see what they wanted to see.

As I learned, it is common for these assessments to be incongruent with the birthing person’s perceptions. Those notes likely had more to do with how I presented — with plenty of support, doing my utmost to follow directions — than however scared, mad, or in pain I felt. This explanation made sense; after all, the triage nurses had seen countless laboring patients. My mental state was bound to be loopy; things would settle down by the six-week postpartum appointment, when I would be screened for depression via multiple-choice worksheet. Besides what was happening in my head, the implications of the qualitative assessment notes were disturbing. Sure, I was compliant: life has consistently rewarded me, straight and white as I am, for navigating systems according to the rules. But what about someone who had reason to distrust the care they were getting?

Even without these clear openings for bias, the conjunction of triage protocols with the state of active labor is laughably bad. The normal range of needs and expressions during birth are often at odds with what most hospitals classify as “coping” or “cooperative,” Lisa pointed out: laboring people may well need to yell, decline to be touched, or have a hard time moving onto the bed for a pelvic exam. They may curse at their partners and caregivers, plead for drugs, throw things, and say they can’t do it anymore. All the above make perfect sense to someone in the throes of labor; yet in a hospital setting, they are likely to precipitate interventions. There is no clear path to ensure informed consent in every case when doing so — in Lisa’s words, “going rogue” — can make the hospital vulnerable to legal action. Trying to reconcile the requirements of all birthing people and a malpractice-shy institution is an impossible task that can strip the humanity not just from birthing people, but also those charged with caring for them.

On some level I’d thought having the baby would refocus me so entirely these stresses would fade away: instead, all that stuff was still waiting for me on the other side.

In a best-case scenario, a hospital birth offers a sense of safety. As a laboring person, you exchange familiar surroundings for a sterile room where crises can be averted before they take hold and pain can be held at bay. What is often skated around is the passivity implied by this level of care. In the early hours of labor spent at home, challenging as they were, I felt like an active companion to my baby’s progress. Once inside the hospital doors, I went from animal self to unquestioning patient, a transition that would leave anybody with a sense of whiplash.

The records gave me another view on that birth, as well as lifting the curtain on the reality of experiencing a major life transition in a hospital. They also prompted me to recognize some of the anxieties I brought to the birth before it started: Covid, isolation from loved ones, work ambitions quashed by caregiving. On some level I’d thought having the baby would refocus me so entirely these stresses would fade away: instead, all that stuff was still waiting for me on the other side.

Since that night almost a year ago, that baby has become a food-throwing tornado-child. Parenting her often feels like a series of reminders of my own inadequacy, something to chafe at, but also to deeply enjoy. I've come to think of her birth as a visceral introduction to this level of mixed experience.

I am holding on to the first lesson she taught me, to repeat back to her someday: when a big, difficult thing derails your sense of self, slow down and look at it closely, even, maybe especially, if that thing and your reactions to it don’t fit into a story you’ve heard before. This holds doubly true if you blame yourself in some way for what happened. And be wary of always being the Good Patient: system-wide changes will only start happening when all of us ask for more.

This article was originally published on