Life

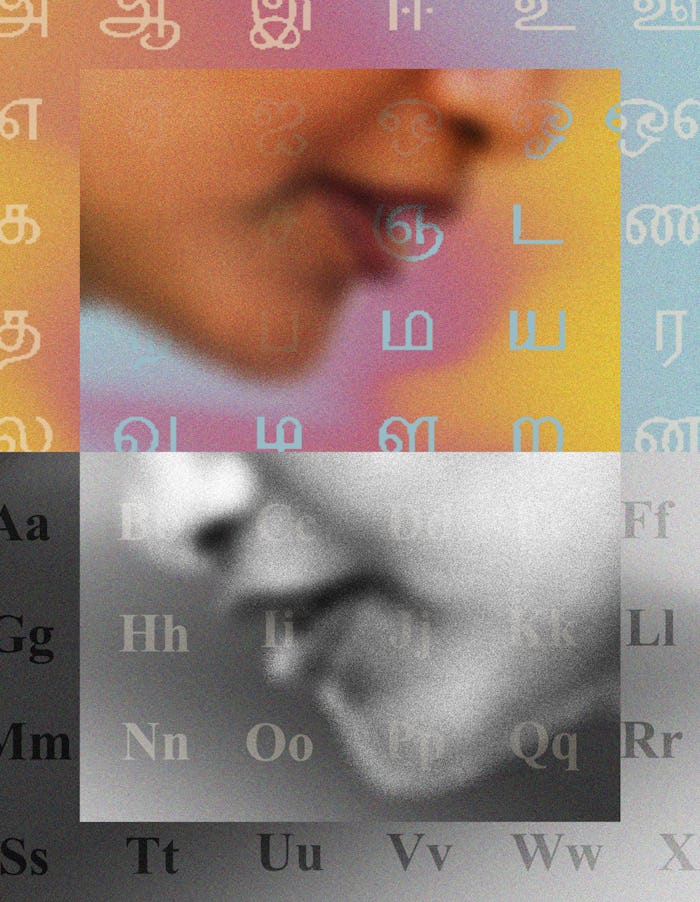

I’m An English Teacher — But I Told My Children I Didn’t Speak English

As Indian immigrants, preserving our language within the four walls of our home felt like a concrete way of clinging to the country we had left behind.

Somewhere around the time our older son’s babbles started becoming intelligible, my husband said to me, “We should only speak Tamil around him, even if we’re just talking to each other. Let’s pretend it’s the only language we speak. That’s the only way this is ever going to work.”

The “this” he was referring to was our goal of making our children fluent in Tamil, our native tongue. As Indian immigrants, preserving our language within the four walls of our home felt like a concrete way of clinging to the country we had left behind. Full fluency was the dream. We weren’t after a passing grasp of words covering rudimentary conversation about family meals and activities. The aim was having rich, nuanced discussions about everything from politics to marine biology. You know, as the average toddler is wont to do.

Look. All I can say is we meant well. Isn’t that how most stories about lies parents tell their kids begin?

I was quick to agree with my husband’s suggestion. I had grown up in a relaxed bilingual environment in Chennai, India. My family slid back and forth between Tamil and English. Our sentences were a cobbled-together mishmash of both languages, where each word was picked based on fastest recall. My husband, on the other hand, had spent more than half of his childhood in California, but his command of Tamil and expansive vocabulary left mine in the dust. English was the language of the outside world that had no place in their home. One of the first times I met my father-in-law, he asked me a question and I responded in English, unaware that I was committing a grave error. He paused, leveled a steely gaze at me, and repeated his question, acting as though I had never spoken.

All evidence pointed to this whole “Tamil good, English bad” method working if we fully committed to it. There was just one problem. I was an English teacher.

When I first moved to this country, the concept of home felt ambiguous, a liminal space that existed mostly in my head. I had left behind the only place that had ever been home, and I wasn’t sure how to start over. Even as the years ticked by and I began to put down roots in a new homeland, I still clung to remnants of Indian life. Cooking my native foods, incorporating salwars and jimikis into my everyday Bay Area wardrobe, speaking Tamil whenever possible — each of these felt like small but uncompromisable gestures to remember where I had come from. This tightrope walk between blending in and standing out co-existed peacefully with walking into a classroom five days a week and teaching adolescents to punctuate their clauses accurately. Until parenthood came along and upended everything.

I had accepted my choice to leave the country where I have memories of growing up and to raise my children in a country that inspires no nostalgia in me. But now that choice had larger consequences.

When our children were 3 and 1, we took an extended trip to India to prepare for my brother-in-law’s wedding. As we entered the airport terminal in Chennai, my older son’s eyes turned saucer-wide. “Amma, everyone here speaks the same language we do!” he whispered urgently. I couldn’t help but be transported back to my own early days of adulthood in America and how set apart I had felt. I remembered the many well-intentioned remarks of “Wow, your English is really good” or “You barely have an accent!” Somehow, I hadn’t considered that my American-born children could feel their own difference just as starkly as I had.

I had accepted my choice to leave the country where I have memories of growing up and to raise my children in a country that inspires no nostalgia in me. But now that choice had larger consequences. It became vital that our home be a safe space not just for our children, but also for cultural remnants we feared would be lost unless we nurtured them.

We couldn’t make our children more Indian, but maybe we could allow them to feel more at ease in their skin. We could teach them to delight in the incredibly nuanced spice profiles of our food, so that when they were teased at school lunch tables, the embarrassment didn’t make them reject their favorite dishes completely. We could share the history of our regional festivals and the richness of our folktales. Together, we could explore the wizardry and incredible wordplay of our mother tongue, in which a single word could morph and expand to contain an entire sentence.

We couldn’t make our children more Indian, but maybe we could allow them to feel more at ease in their skin.

All of this required concerted, sustained effort. We kept our family exchanges strictly in Tamil. I sometimes had to covertly text my husband for the Tamil translations of English words before inserting them into a conversation with the kids. When either of them flaunted the English they were learning at preschool, my husband and I would feign ignorance. “Appadi naa enna?” we’d ask. “What does that mean?”

I knew that the minute my children found out what I did for a living, this jig would be up. My choice of career developed a gentle warning glow around the edges, a sign of potential trouble ahead. But still, for years, I stayed quiet. A complicated combination of guilt and honorable intent kept this secret alive in our household. It was nearly impossible for me to explain our rationale to anyone except my willing co-conspirator in our ongoing scam. And so, we kept it to ourselves.

It’s not that I had shame about my job. I got to spend my days annotating Shakespeare and Orwell with moody eighth-graders, grading essays and despairing over over-worded, under-reasoned arguments. My evenings, on the other hand, were filled with games of hide and seek and our own Tamil version of Zingo. Initially, as untruths went, this one felt white lie adjacent. No one was being hurt. However, the more I thought about it, the harder it became to shake the self-doubt. What kind of hypocrisy was involved in correcting the grammar of 13-year-olds if I couldn’t do the same with my own sons? I mean, there had to be a limit to how much longer I could bite my tongue in response to our 3-year-old’s “What is doing?” (A question he repeated approximately 400 times daily, by the way.) Was this experiment really worth it? How long would our kids care about speaking Tamil before it became an annoyance, or worse, an othering experience?

A few months before our then-5-year-old started kindergarten, with those questions in my ears, I finally decided it was time. I sat him down to explain that Amma was an English teacher. “I know we don’t speak it at home, but that’s the language I used for learning all through school, and it’s the subject I chose to study in college. I’m sorry I didn’t tell you before. We’re going to continue speaking only Tamil at home because this is where we keep practicing it, OK? We should be proud of where our family comes from.”

I want them to be able to communicate easily, not just with their grandparents but with everyone they encounter. I want to be able to sit down as a family to watch Tamil movies together without having to translate the dialogue. Really, I want them to experience their cultural inheritance without needing subtitles.

My announcement wreaked definite confusion, but to my surprise, it passed relatively quickly. My older son was mostly amused. “Ha, I knew that already! I’ve heard you speak English to your friends before!” Our toddler was too young and clueless to realize his mother had pulled back the curtain of parental omniscience while he wasn’t looking. My husband had the hardest time taking our new reality in stride and needed a short doubt/mourning detour before he could rejoin the rest of us.

As the children of first-generation immigrants, our sons are stuck in the in-between. Their notions of homeland are going to be different from our own. There are so many communities they will come to belong to, and many of them will have nothing to do with their ethnicity or racial background. And that is exactly how it should be. But I also want them to feel connected to their Indian heritage. On annual visits, I want them to be able to communicate easily, not just with their grandparents but with everyone they encounter. I want to be able to sit down as a family to watch Tamil movies together without having to translate the dialogue. Really, I want them to experience their cultural inheritance without needing subtitles.

But ultimately, what I want them to have, what would make all of this worthwhile, is the knowledge that as long as they reach for it, Tamil will always belong to them.

Like us, our children are now working through what it means to be bilingual. Our older son is able to make the back and forth transition more easily. After two years of refusing to respond in Tamil when we were in public, he’s now comfortable inhabiting both languages without feeling self-conscious. Our younger son, whose English was as shaky as poorly set gelatin until he entered kindergarten in the fall, is now staging a small rebellion. “I don’t know how to say all those things in Tamil,” he pouted last month, when I asked him to tell me about the art project they were working on in class. “I don’t have those words, and you’re making it too hard.”

All I can do now is encourage him. “Just try,” I said. “The words are hiding inside there, and if you have trouble finding them, we’ll help.”

Language sometimes feels like a puzzle to solve, and it’s harder when it becomes yet another marker of difference. With or without our well-intended, if ridiculous, deception, our boys have a lifetime ahead of them to wrestle with the multiple complex identities that live within their brown bodies. But ultimately, what I want them to have, what would make all of this worthwhile, is the knowledge that as long as they reach for it, Tamil will always belong to them.

Purnima Mani is an impatient parent, middle school English teacher, intrepid home baker, and fledgling writer. Her skills in each of these areas tend to be eclipsed by her enthusiasm; nevertheless, she perseveres. She lives in Northern California with her husband, two children, and a very opinionated rescue dog.