Books

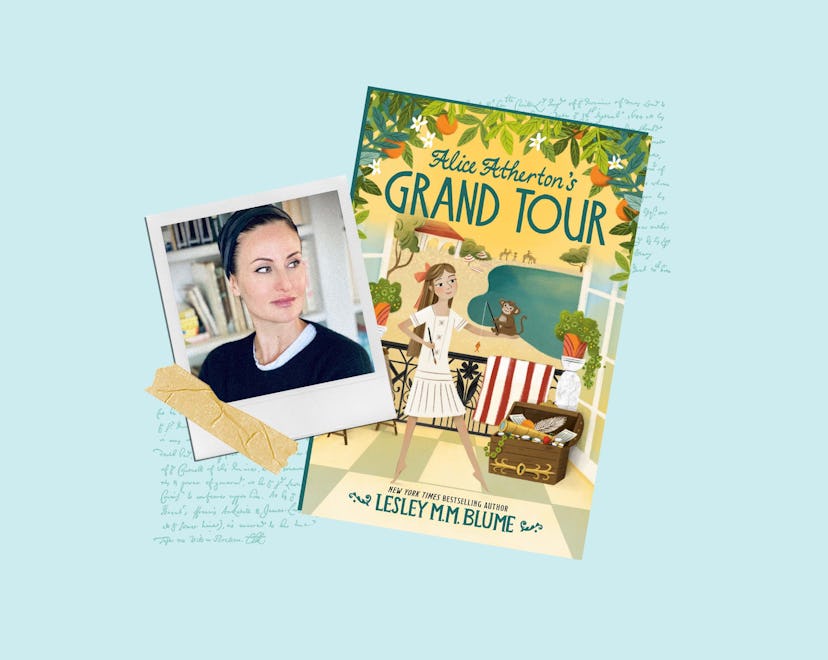

A New Children’s Book Lets Picasso, Hemingway, & F. Scott Fitzgerald Teach The Lessons

In Alice Atherton’s Grand Tour, Lesley M. M. Blume tells the story of a girl who discovers the magic of the Lost Generation.

I was in college when I first read A Moveable Feast, Ernest Hemingway’s memoir about Paris in the 1920s, and it instantly became my fantasy of adulthood. There could be nothing freer, more sophisticated, than being an American artist abroad, living in a shivery apartment in a dodgy neighborhood, visiting Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas at home, and scribbling for hours in a notebook while sipping café crème. But Lesley M. M. Blume, a journalist and Hemingway biographer, saw that this thrilling expat world was not so much a blueprint for adulthood, but the perfect setting for a children’s book.

Alice Atherton’s Grand Tour (Random House), a charming chapter book for young readers, isn’t set in Paris, but rather in the decidedly unshivery south of France. Alice, a 10-year-old American, is sent to live with Gerald and Sara Murphy in their house on the French Riviera, Villa America. The Murphys, who were the real-life inspiration for the protagonists of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is The Night, were rich and beautiful Americans whose friends included the Fitzgeralds, Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, and many others. They were also devoted parents to three children, who spent formative years in this bohemian paradise.

In each chapter of the book, Alice spends time with a visiting friend of the Murphys — Picasso, Igor Stravinsky, and Coco Chanel included — and learns a lesson about life. For Blume, it was a respite from the kind of books she has been writing for adults. Her most recent was Fallout, about the U.S. coverup of the effects of the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Before that, it was Everyone Behaves Badly, about Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and the decidedly R-rated adventures of his friends in the “Lost Generation.” (It wasn’t, however, her first children’s book; Blume has previously written six of those.)

I recently sat down with Blume over Zoom to ask her about bringing these legendary artists to young readers and what we can all learn from the parenting style of America’s most glamorous bohemians.

What made you think this was a good topic for a children’s book?

I was working on a book about Hemingway in the ’20s and the Murphys were a really big part of it. And their world was so intoxicating, creative — it was like taking a warm bath, the most beautiful bath, and you never wanted to get out of it. And there was a real sweetness to it also, because they were a highly dedicated family. They were extremely wealthy parents, and back in the day, you would have a legion of help to raise your kids, but they were really hands-on. They made life into an art form and they made family life into an art form. There was all this material that was really not relevant to my nonfiction adult book but I just thought could make an incredibly sweet children’s book.

How did you end up settling on a way to tell the story of the Murphys?

Well, you can’t just give a description of the Murphys’ life. Sara and Gerald Murphy, they were a young American couple who were living at this beautiful villa in the south of France when it still wasn’t a very popular tourist destination. And they created their dream home called the Villa America. They had three beautiful, brilliant, creative children, and they even had a pet monkey. So, how do we tell the story of them that doesn’t sound like just a biography? So I dreamed up a young American girl, a family friend whose mother has died in the aftermath of the 1918 flu. She’s sent over by her father to live with the Murphys for a summer to kind of recuperate and learn how to live life again. And who better than to teach a young girl how to live in the moment and appreciate life’s pleasures and beauties than Sara and Gerald Murphy and their family?

And then another thing that’s extraordinary about the Murphys was that they were friends with some of the most important creative figures of the 20th century. So, Picasso was a regular guest, and Hemingway was a regular guest and the Fitzgeralds. And Coco Chanel overlaps, Stravinsky. Diaghilev and the Ballets Russe. I mean, you name it, they were at the Villa America or overlapped with the Murphys in Paris at some point. And so I just came up with the idea that these luminaries would visit over the summer, and each of them would give the children a life lesson.

For example, Picasso takes the children to a junkyard and they gather all sorts of objects to create art from, and it completely changes their worldview about what is art and how we find beauty in the everyday, how you can find beauty and potential in even cast-off objects.

Romper: It’s not often you find a children’s book with a chapter about Picasso and Diaghilev.

Lesley Blume: No. I mean, all of these creatives, they were striking chords. They were not only reinventing ballet and visual art and writing, but people did have violent reactions to them. And that was compelling to me when I was writing about them in nonfiction. But even in this children’s book format, they’re not easy figures. I’m certainly not whitewashing their flaws and their less savory characteristics.

But it was just so damn nice to be with them again after writing about nukes for five years.

Romper: Of all the periods in history, this is the one that feels kind of like sipping a glass of champagne. Just this idea of these people who are able to throw themselves completely into the creation of art and take themselves so seriously as artists — it feels like a fantasy to me. And I know there were many dark parts of it for many of them, too.

Lesley Blume: I mean, the Murphys invented the fantasy. They knew it was fantastical. And one thing that resonates with me is that it was a period of extreme opportunity. I mean, as you were saying, yes, they were all licking their wounds from a ghastly war and also a pandemic, but it was a really extraordinary time of promise and there was a capacity to appreciate beauty, to push boundaries and art in a way that was kind of noble in a way.

I don’t gloss over the scars of the war in Alice Atherton. In fact, it comes through quite frequently in the artists with whom the Murphy children and Alice spend time. They have been war-scarred, and there’s a lot of apprehension on behalf of the adults for the future of the children. Is the future going to bring more for them of what the past dished up? I believe that difficult history needs to be approached in a very specific way with young readers, but I certainly don’t think it should be ignored. And so that was important to me, that this book be laced with those themes and events.

Romper: So obviously you drew on all this history to write this book, but what did you draw on from having a little girl?

Lesley Blume: The first six books that I wrote for young readers [were] before I had a child of my own. I drew on my own rather distant memories of childhood and childhood sensibilities to write all of those books. And all of a sudden when I was writing Alice, I had a 9-year-old girl. Once in a while, I would run dialogue with her. I would be one of the characters, and I would have Oona be Alice. And I put whole chunks of that dialogue in the book.

I have a photo of her reading the manuscript, and nobody could come near her. She was a bloody critic. She would say, “This is a little boring, Mommy. I think you really needed my help with this dialogue. Let’s work on this.” I knew if I could hold her attention with it, then I had something to work with, and if I wasn’t holding her attention, then I was on the wrong path.

This article was originally published on