Life

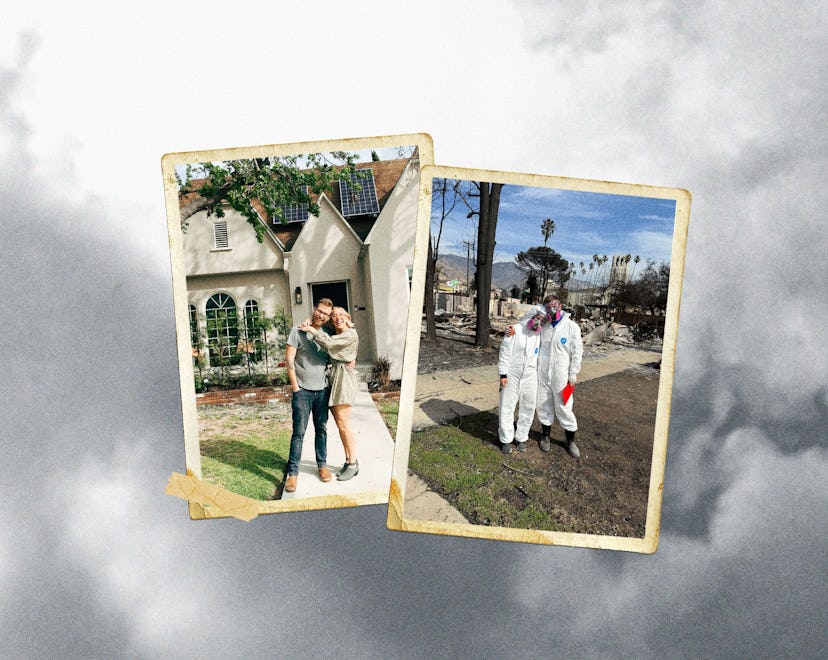

The LA Fires Destroyed Our Home & Everything In It. Where Do We Go From Here?

How to make sense of it all? A world where climate change isn’t going to happen; it’s happening, not to someone else, but to me and my young children, now.

I peered out in the dark, the barely begun Eaton fire still miles away from our house: “If our house burned down, what would you miss the most?”

“Kira. All of Altadena would have to burn down for our house to burn. Our house will be fine,” my husband said, squeezing my hand.

We were in our friends’ guest room because our hyperlocal Altadena Facebook meteorologist Edgar McGregor had warned the neighborhood of potentially dangerous winds coming that night, reaching up to 100 mph. Instead of facing a certain power outage and potentially having a renegade branch break through our windows and into our heads while we were sleeping, we moved all of our outdoor furniture inside and packed up our kids and a simple overnight bag. Around 3 p.m., we headed to our friends’ house for what became the least-joyful sleepover of all time. The weather event was just windstorm until around 6 p.m., when we started seeing reports of fire in our local mountain range. Still, it was in the forest, far away from our front door.

I took mental inventory of our home’s contents and began listing aloud the things I would miss. We fell asleep holding hands but woke up every hour to the other one nervously checking the WatchDuty App. Around 2 a.m., the app showed the fire moving in the immediate surrounds of our block (though we never received an evacuation notice), and it became very clear that our house was very possibly not going to make it. The winds had not died down since we had fallen asleep, and on our phones, we watched the fires ripping through our beloved Altadena with unchecked violence due to the unprecedented Olympian speed of these Santa Ana winds.

In the morning, it was impossible to tell, with the little information we could gather online, which houses were spared. The fires continued all day, and all day we wondered: What was to become of us? Was our house still standing, amid a town that had been condemned to ash? Or was it gone, along with the now 9,500 others? As it turns out, nearly all of Altadena did, in fact, burn down.

“It’s gone,” she said, her voice solemn and cracking. “It’s all gone. I’m so sorry.”

In Altadena, I had finally found my perfect version of Los Angeles: close enough to the action but far enough away to feel I was living in a mountainside retreat. It was LA’s best-kept secret: a middle-class neighborhood where it wasn’t uncommon to see someone riding around on a horse or to run into someone I knew at the beautiful waterfall hike minutes from my front door. We purchased our house there less than three years before, and we had just spent half of our savings completely renovating the backyard.

The following night, Jan. 8, we tried to go see our house, to see if it was on fire or spared. But at every possible street entrance, there were police blockades keeping us from going in, as the fire was still active and spreading. We wore masks in the car, but the smoke was so thick I nearly vomited, gripping the passenger door with nausea all the way back to our friends’ house — the site of what was clearly now going to be a very, very long, very depressing sleepover.

The next morning, our friend offered to go to our house and let us know if it was still standing. She tried to FaceTime us, but the service was terrible, smoke and fires still raging in the area.

“It’s gone,” she said, her voice solemn and cracking. “It’s all gone. I’m so sorry.”

She sent me a picture of the fairy door I had nailed to our front-yard tree for the kids, the one thing she was able to salvage. There was nothing but rubble where our house used to be. Once I calmed myself down and consoled my sobbing kids, I zoomed in on the pictures she sent. Our pool was black with toxic ash. Half a Peloton was clearly visible among the wasteland, a chilling apocalyptic relic. The firepit we had just installed in our new yard looked untouched. Our massive air conditioning unit was half-melted. These weren’t my things; they were items for sale in a Mad Max catalog.

I couldn’t believe this was possible. For one, our houses were in such an urban area; we purposefully chose it for its walkability score of 83/100!!! A house up in the foothills made me nervous, so I felt at ease signing papers on a house whose windows had a clear view of the beautiful Altadena mountains but far enough away that it wouldn’t ever pose a threat. We were miles down from the forest. Unthinkable.

It’s now been more than a month since the fire, and every day I remember something in my home that I’ll never see again. My grandmother’s dresses from the 1950s that I cherished so dearly and for so long, from the time I played dress-up in her closet all the way to wearing them as an adult. The unbelievably sweet, loving letters my parents wrote to me when I was away at various summer camps. The wondrous vintage clothes I’d been meticulously collecting for my kids since they were babies, separated into bags for each year of their lives, waiting for them to turn 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. My family photos, almost all of which my parents had entrusted me with in recent years as they downsized their homes — all the photos from their childhoods and mine. Gone, all ghosts.

All my children’s drawings, all my children’s first notes. The sea urchin my daughter drew for me that I had taped up next to my pillow — she called it my SEA URGENT. Those hit me the hardest, of course.

I host a PBS travel show called Islands Without Cars, for which I’ve spent years interviewing residents of far-flung islands and bringing back treasures from their remote shores. Things I can never in a million years replace. Tiny ceramic houses from artists on Burano, Italy. A painting from a renowned British painter on Hydra, Greece. World War II relics from a museum in Helgoland, Germany. A painting I made of the Dutch seaside for my unborn son (it was so unskilled, the only acceptable room for it was a nursery, and it has hung in his room for seven years) on Schiermonikoog, Netherlands. A sweatshirt commemorating my participation (and 33rd place) in the 2022 World Stone Throwing Championships in Easdale, Scotland.

I don’t have the space here to write the eulogy that my house deserves. A 1924 gabled-roof English revival beauty with an oddly shaped pool that we hosted a million parties in. The secret attic of my Nancy Drew-obsessed childhood dreams. The fireplace we played a million rounds of Hoot Owl Hoot beside. The flower mural I hand-painted on my daughter’s bedroom wall. The gnome I painted on my son’s wall, a triangular-hatted guy proudly holding a branch of the rowan tree for which my son was named. The century-old Palladian windows that let in the most beautiful golden light in the afternoons. Vanished.

On Day 4 post-fire, we drove to a resort in Palm Springs that was offering special evacuee rates. About 20 families from my online mom group were also staying there, fleeing the toxic air in Los Angeles or houses that had also burned down. All over the hotel grounds, we pretended to pay attention to our children while we frantically dealt with insurance, fielded concerned family calls, managed work from our tiny screens. I attended a 6 p.m. sound bath in a conference room with tens of other evacuee moms, tears streaming down my face as the singing bowls reverberated around my tense jaws. I received a million tearful hugs from moms I had either never or barely ever met before that week. I pretended to enjoy eating s’mores with my kids, as I glumly stared into the fire and thought, What is to become of us now?

At the hotel, I looked over at our aging dog and remarked that she hadn’t barked in a very long time. “That’s because no one has come to our door in a long time,” my daughter reasoned. “And now, they never will!” she exclaimed, her humor too gallows for her six little years. “Because we don’t even have a door anymore!” She said it all through a mouth full of pancake, twisting the knife.

In the strangest plot twist, I had already booked an acting job that was set to film in Cape Town, South Africa, exactly one week after the fire burned my house down. I went to Herculean efforts to secure an emergency passport so that I could still do the job (mine had, of course, burned). I left my shell-shocked husband and children in Los Angeles and flew to join my fake husband and my fake children, in my fake house, on set. I smiled and nodded and pretended to generally be alive in any way.

At the end of the shoot, I spent two days on a safari I had booked B.F. (Before Fire).

I’m unable to do what part of me really wants, something impulsive like move to a remote island, because I have children, a husband, friends, responsibilities, and a career, all of which are tethered to a city that just broke my heart.

For two days, at dawn and dusk, I got in an open-air vehicle and drove around a national park the size of New Jersey, searching for animals. I saw elephants, impala, vultures, water bucks, jackals, hyenas, warthogs, zebras, giraffes, kudus, wild dogs, and lions. I learned that a group of zebras is called a dazzle. A group of giraffes is called a jenny. All that was asked of me was to sit in total silence and search for the majesty of charismatic megafauna.

Who was I, in all this? Was I the dung beetle we saw on the side of the road, rolling an impossibly large pile of sh*t uphill? Or was I the kudu, running away terrified at the sound of encroaching danger? Obviously I wasn’t the lion; I had no power here, or there, or anywhere.

How to make sense of it all? A world where climate change isn’t going to happen; it’s happening, not to someone else, but to me, now. An eight-month drought combined with the strongest LA windstorm since 2011. The Santa Anas that Joan Didion wrote about in 1968 — “The winds shows us how close to the edge we are.” — and that Randy Newman paid tribute to in his song “I Love L.A.”

I don’t know how to be a climate refugee, and yet here I am, with a new, consistent left-eye twitch and a relaxing new nightly nightmare programming schedule theme of trying desperately to find a place to live, running and racing to find safety for me and my kids. I wake up every morning clutched into a fetal position, my neck so tense I can no longer look all the way to the right.

Where will we go? What will we do? Is Los Angeles tenable any longer? Or was it never, actually, and we have all just been fooling ourselves? Someone, give me back the blinders of my 2024 ignorance.

On my last safari, as an elephant positioned itself on the road in a charge position, I nervously asked the guide if he had a tranquilizer gun in the glove compartment in case an animal attacked the (quite vulnerable) Land Cruiser.

“No, we are not allowed to have any of that,” he said.

“But what if there’s an attack out of nowhere?” I asked, just a little panicked, watching the elephant square off in front of us. Statistically speaking, it would be crazy for my house to burn down and get attacked by an elephant in the same week, but 2025 has taught the brutal lesson that anything is possible.

“There is never an attack out of nowhere. As long as we are watching, we will be fine.”

The guide then raced the car toward the elephant in a display of dominance, and the elephant took the bait, trotting away from our car and off toward his small herd, nonplussed.

“Nature always gives warnings,” he said, taking his foot off the gas.

I ruminated on this as we bounced our way back to our huts, still alive. Los Angeles has, in fact, given us a titanic warning. It certainly isn’t the first warning it’s given its foolhardy inhabitants, we seasonless, cinema-obsessed, UV-loving dunces, and it certainly won’t be the last. Everyone I know who lost their home in the fire, my entire beautiful community of Altadena, not to mention the Palisades, seems stunned and rooted to the spot, afraid to leave the city for which we’ve braved earthquakes and fires and ghastly housing prices and dreadful traffic.

And yet, for all this foolhardy commitment, we’ve been betrayed. Cuckolded, it feels like. And stupefied. I walked into the FEMA services site two weeks ago and burst into tears. At each kiosk, I forget why I sat down. I desperately apply to schools in neighborhoods I haven’t chosen to live in and would never have chosen to live in, and I burst into tears in their enrollment offices, having to explain all over again what happened to us, to our family, to our home, to our beloved community. I attend a grief support group, where one woman holding the talking crystal tearfully reveals she is staying at an Airbnb in Burbank, and there is a collective groan. No one wants to live in Burbank.

The question is what are we meant to do with this warning. I want to write the whole damn ordeal down on a piece of paper and burn it, “letting it go,” killing it off, but that would be too on the nose, not to mention ineffective, so instead I sit with it, this ashen lump in my throat, in my heart. I’m unable to do what part of me really wants, something impulsive like move to a remote island, because I have children, a husband, friends, responsibilities, and a career, all of which are tethered to a city that just broke my heart. So here I sit, doorless. I loved LA.

Kira Cook is a writer, actor, and host of the PBS travel series Islands Without Cars. She lives in Los Angeles and you can find her on Instagram @flamelikeme.