Media

Stop Saying Women “Dropped Out” Of The Workforce. We Were Pushed.

Now more than ever, the media feeds our worst beliefs about working motherhood.

Last year, I pitched a panel to a conference on women and podcasting about the realities of working motherhood in America and the need to find more nuanced and thoughtful ways to cover it. I submitted the proposal while I myself was pregnant with twins, planning to fly across the country to attend said conference, and working on the second season of my own podcast. The organizers turned me down. “We just don’t think a whole panel on issues facing mothers would be relevant enough” was the explanation, despite the fact that 80% of women become mothers.

This is just one example of the gobsmacking anti-mom bias I’ve witnessed researching and reporting on motherhood. After all these years, the idea persists that mothers’ struggles to work and support their families are at best a sideshow. But what really revs me up, having spent my career in media, is that I can say unequivocally: We, the media, help perpetuate it.

Proof of our contribution may be on your screen right now. See the reams of content for mothers on lunch-packing strategies and easing tantrums, compared to the near nonexistence of political or financial content geared specifically to women raising children. See how almost every stock photo that runs alongside a story about working motherhood is of a pretty, white-collar white lady with a laptop and a baby on her lap, a position in which no one has ever completed work.

Allow me to suggest some more accurate language for news outlets to use. How about, “forced out,” “pushed out,” or, my favorite, “thrown out of a five-story window.”

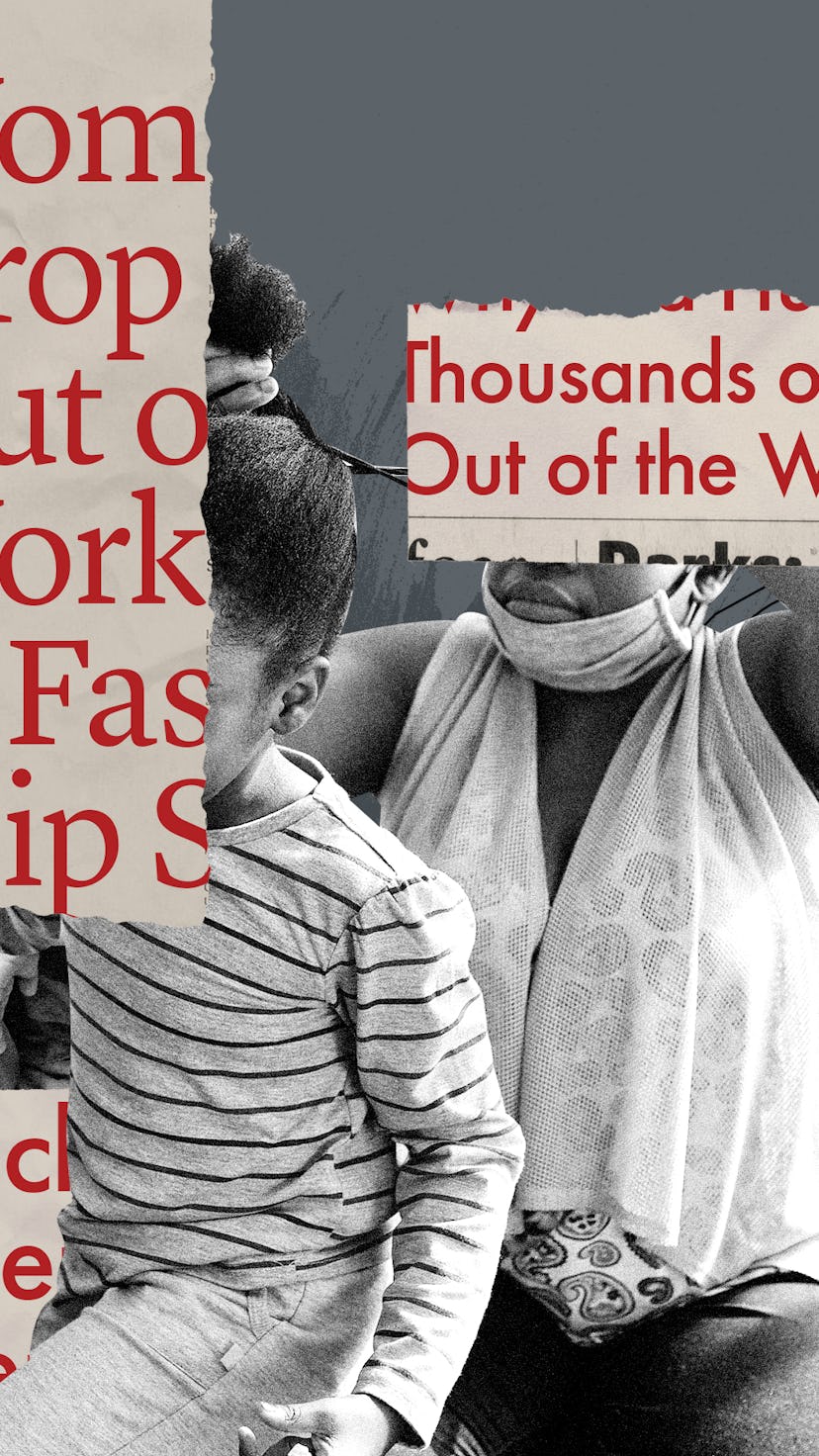

And I saw it in the late summer coverage of “the female recession,” the disappearance of close to a million women from the workforce in August and September alone. “Why Did Hundreds of Thousands of Women Drop Out of the Work Force?” asked The New York Times. “A shocking number of women dropped out of the workforce last month,” declared CNN. (Note: No working mother was shocked.) Bloomberg notified readers, “Women Drop Out of Workforce at Fastest Clip Since Virus Peak.” CNBC announced it as, “More than 860,000 women dropped out of the labor force in September, according to a new report.”

Here’s the problem: Framing women and mothers as “dropping out” fundamentally misunderstands what is happening to us and reinforces cultural ideas about motherhood that do not benefit anyone. Sociologist Caitlyn Collins, in her cross-cultural comparisons of motherhood, has found that, despite having deeply inadequate public support systems for mothers and families and a large gender wage gap, mothers in America blame themselves for the difficulties they face and see figuring out work and caregiving as solely their responsibility.

Mothers in Europe don’t grapple with the same feelings of guilt and inadequacy. Instead they have higher expectations that spouses, employers, and the government can and should support them in caregiving.

The phrase “drop out” feeds into this singularly American view of motherhood. It suggests a personal decision, and its unflattering connotations imply that those who leave work lack perseverance, grit, or the ability to work hard enough to succeed — all highly prized traits in our culture. This is just not an accurate description of what’s going on.

We are in the middle of a massive, nationwide recession that disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color. That 860,000 number doesn’t even capture how bad things are for mothers specifically. Further data revealed an even more devastating picture: There were 1.6 million fewer mothers in the paid labor force in the summer of 2020 than there were in the summer of 2019.

This happened because our federal government has failed to get this virus under control and has provided none of the desperately needed resources to help public schools open safely or creative efforts to provide child care or supervise virtual learning so parents can work. It has not bailed out child care centers or provided comprehensive job protection, adequate paid family leave plans, or child care subsidies. The working mothers who left the workforce are not just a bunch of people who made independent, personal decisions. Because we’ve been largely abandoned by our government, many mothers actually have no choice at all.

Allow me to suggest some more accurate language for news outlets to use. How about, “forced out,” “pushed out,” or, my favorite, “thrown out of a five-story window” of the workforce. Every news story about our professional demise should, from the headline on, report the most important fact: This is not about personal failing. Specific policy choices are directly responsible for women leaving jobs that provide for their families and careers they have spent years building, which they know (because the media have reported this accurately, over and over again) that they will almost certainly not be able to reclaim.

Mothers in Europe don’t grapple with the same feelings of guilt and inadequacy. Instead they have higher expectations that spouses, employers, and the government can and should support them in caregiving.

The way journalists are talking about this almost rivals how they describe the way women are ricocheting between their work and household responsibilities during the pandemic. It is almost always covered as though being overwhelmed by personal and professional responsibilities is casually inevitable. I think we should examine this assumption.

In a well-reported piece from NPR, labor economist Martha Gimbel describes how moms are living: "Someone has to supervise the learning. Someone has to deal with the cooking. Someone has to deal with the cleaning, and it's falling onto them (emphasis is mine). And so they can't make choices that they want to make because they're being restricted in all these ways."

I completely agree with Gimbel’s larger points and sentiment. But... falling from where? The sky? Accidentally? Describing the unpaid labor mothers are doing during this time as “falling to them” does not convey that, just as our elected officials chose not to enact public policy to support mothers, it is a choice for male partners, who directly benefit from this labor, not to do their fair share.

When men choose to “let” mothers do most of it, they get more time to work, advance their careers, and train for that post-COVID triathlon. They get to do the “fun stuff” of parenting, like a trip to the playground, followed by ice cream, while the mother gets a “break” from caregiving to fold laundry, print packets for virtual school, and reschedule the doctor’s appointment.

So let’s describe this as the direct affront that it is. Instead of saying most domestic work is “falling to” mothers, let’s use “unfairly burdening,” “unequally saddled on,” or the succinct “dumped on.” Those would all be much more accurate and would challenge the idea that this is all accidental. It’s not.

The lifestyle desks of major newspapers, especially, seem to love a “juggle.”

If I could fantasize about a very simple benefit to come out of this pandemic, it would be to retire the word “juggle” as a descriptor of motherhood. The lifestyle desks of major newspapers, especially, seem to love a “juggle.” I loathe it. It’s unserious. It’s something a clown does, and I find it a belittling way to describe what it actually takes to manage the demands of a job for pay with society’s ever increasing demands on mothers. As the mother of three children under 6, let me tell you, I don’t juggle. I do “executive level multi-tasking.” I “solve complex and competing logistical challenges.” I “lead critical areas of household operations.” All that we do as modern mothers requires skills that are worthy of any resume. Let’s use our words to claim that.

“Juggle” commits the additional sin of reinforcing one of our worst beliefs about motherhood: that we are just one life hack or schedule tweak from “making it all work,” and that it’s on us, individually, even in a pandemic, to figure everything out. In March, in a piece on The Conversation about “juggling” during the pandemic, a working mother presented a dizzying series of color-coded Excel sheets to show how she was attempting to manage work and virtual school. She described how she had created, in her words, “a manic schedule and we are trying to adapt it each day to make it work.” The piece ended with the cheery hope that, with some flexibility, we would all get through this seemingly temporary period. By summer, the reality was setting in. In an article from PBS, the message was now that “the juggle” was “not working.”

Perhaps it never was. And perhaps we need media coverage that better explains how sexism, unequal relationships, policy failures, and employer indifference has led us to this moment. As PBS’ Laura Santhanam writes in that piece about the ongoing misery of this work-family conflict, “To experts, the only small cause for hope is that the current crisis may inspire calls for a cultural change.”

My hope is that maybe part of that cultural change will be how we talk about the issues mothers face. We don’t need more color-coded schedules. We need more galvanizing, clear-eyed, big picture realism.

Katherine Goldstein is an independent journalist and the creator of The Double Shift, a podcast, newsletter, and community. Sign up for the newsletter here, about challenging the status quo of motherhood and the forces that shape family life in America.

This article was originally published on