There Was No Easy Way To Make My Wife The Legal Parent Of Our Baby

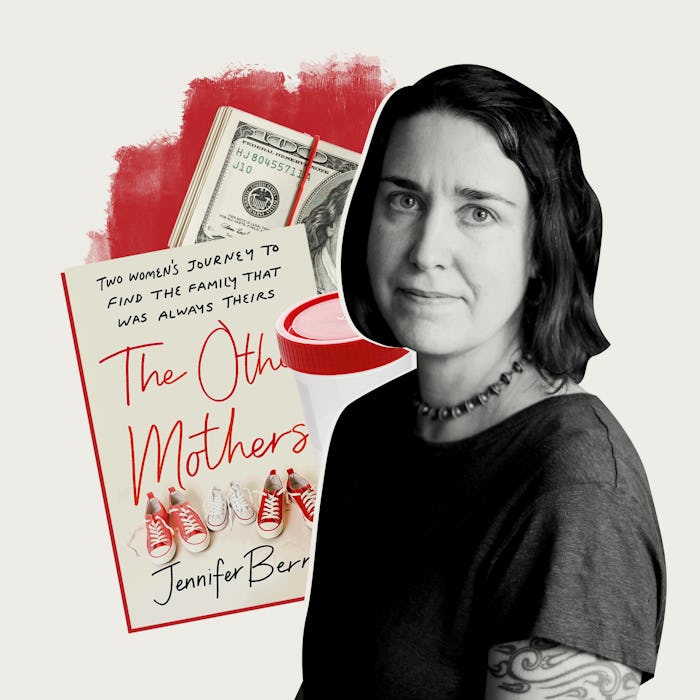

An excerpt from Jennifer Berney's new memoir, The Other Mothers: Two Women's Journey To Find The Family That Was Always Theirs.

“Do me a favor and get a lawyer.” Our doctor's request followed me during the last months of my pregnancy. My wife, Kellie, and I had always planned to make Kellie a legal parent, but the doctor’s show of concern that day in her office had added some urgency. It was true that I trusted our donor, Daniel, and his partner, Rebecca, to honor our agreement. I couldn’t imagine any circumstance where Daniel would suddenly decide he wanted to sue us for custody. I also trusted both Kellie’s family and my own— there was no relative on either side who would, for instance, decide if I died that Kellie had no right to raise our child. Or at least I didn’t think so.

But there were two other things I knew. Of all the people who wound up in some kind of epic legal battle over their children, very few of them ever saw it coming. And I knew that our status as a queer couple made Kellie’s role extra vulnerable, tenuous at best in the eyes of the law.

If we had been a straight, married couple who had conceived with donor sperm — even if that sperm had come from a community member — no one in the delivery room would have asked any questions.

There was no easy way to make Kellie a legal parent. If we had been a straight, married couple who had conceived with donor sperm — even if that sperm had come from a community member — no one in the delivery room would have asked any questions. My husband’s name would automatically be listed as father. But in our actual circumstance, Kellie’s name would be nowhere on our child’s birth certificate, even though we could both attest without hesitation that we were a couple and that we had conceived this child with the intention of raising it together. If we wanted Kellie to have any legal rights, we would have to buy them.

Even as of this writing, when all 50 states and the federal government recognize gay marriage, and when most states have provisions that allow a nonbiological parent to appear as the second parent on the birth certificate, LGBTQ+ advocacy groups uniformly recommend second-parent adoption as a necessary step to protect the intended family relationships. As Cathy Sakimura, family law director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, told The New York Times in 2017, “You can be completely respected and protected as a family in one state and be a complete legal stranger to your children in another.”

And so, Kellie and I pursued a second-parent adoption.

There were lawyers who specialized in LGBTQ family law, but they all lived in Seattle and seemed like designer lawyers, ones that might cost us two or three times what we would pay if we were willing to trust someone local and unspecialized. We asked a friend of a friend, who had a law degree, if she might know anyone who could help us. She thought about it for a minute, shrugged, and said, “I don’t know — my neighbor, maybe?”

Her neighbor, it turned out, practiced family law from a small A-frame building less than a mile from where we lived. She was a hefty woman who shook our hands with a firm grip and sat us down on a leather sofa. She eyed my belly.

“I had twins,” she said. “They’re in college now. You’ll probably breastfeed, right?”

I nodded.

If we wanted Kellie to have any legal rights, we would have to buy them.

“You’re in for it. I never left my armchair. I just sat there with one kid on each boob and a Diet Coke on each armrest.” I could picture her filling an armchair, shirtless. Strangers offered up these sorts of details readily now, anytime I was with Kellie, never when I was alone. They struck me as the speaker’s way of compensating for our difference, an effort to offer something vulnerable and weird since we — because we were visibly queer and expecting — had shared something vulnerable with them. Being gay sometimes felt similar to conversing with a person who had just walked in on you in the bathroom. You might pretend together that everything is normal, but it feels like they’ve got something on you.

Our lawyer spread a bunch of paperwork across her desk and walked us through the process. Daniel would need to sign away his paternity rights. That part was easy: One standard form and a notary stamp and he would no longer be the father. We could just drop it in the mail with some instructions. Making Kellie the second parent would be harder. It would involve not just a pile of paperwork, but two visits from a social worker. A “home study,” it was called. A stranger would come to our home to study us.

She wrote the name of a social worker on a sheet of paper. “I know the whole thing is stupid,” she said. “But she’s one of you, so she won’t give you any trouble.”

“One of us — does that mean she’s gay?” I asked Kellie on the ride home.

“F*ck if I know,” she said.

The social worker was apologetic too. “I’m sorry I have to do this,” she said. She sat at our kitchen table, which we had cleared off in preparation for her visit. We had cleaned for her, like people do, even though it struck me as silly. Would it matter if there were a pile of bills on the kitchen table? Would some dog hair on the floor indicate that we were unfit to care for our own child?

With her permed blond hair and floral dress, the social worker didn’t immediately set off my gaydar. She asked us how we felt about spanking, how heavily we drank, and if we’d ever been convicted of any felonies. And then, as she was packing up her briefcase, she suggested that we all get together once the baby was born. “My daughter’s 3,” she said. “She doesn’t know any other two-mom families.”

At the end of the day, we spent nearly as much on making Kellie a legal parent as we would have spent on a round of IVF or a down payment on a foreign adoption.

My heart sank a little when she said it. Her voice was tinged with loneliness. She seemed like a person I would have been happy to meet in any other context. I wanted to know some other two-mom families too. But I didn’t feel like being friends with the social worker I’d never asked for, the person who would soon be sending me a bill for visiting my home and writing a report that assessed whether or not I’d be an adequate parent. I didn’t want to feel that way about it, to transfer my frustration with the system onto her, an agent within the system who wanted to help us. I didn’t want to, but I did.

At the end of the day, we spent nearly as much on making Kellie a legal parent as we would have spent on a round of IVF or a down payment on a foreign adoption. I had planned on dropping a thousand or two on these legal arrangements; I had never planned to pay $10,000. In my mind I enumerated all the reasons we were lucky: We both had jobs that paid enough and our home carried a mortgage lower than what most people paid for rent. Our community had come through with sperm before we had gone into deep debt. I had health insurance to cover the costs of my pregnancy. I knew for a fact that there were plenty of queers who became parents without any of these benefits. They sourced sperm on the fly and trusted love and community to protect them, not the law. Even $10,000 later, I still wasn’t sure that I trusted the law to protect me, but I’d rest a little easier knowing I’d done what I could.

You can order a signed copy of The Other Mothers from Browsers Bookshop, an indie bookstore in the author's hometown of Olympia, Washington.