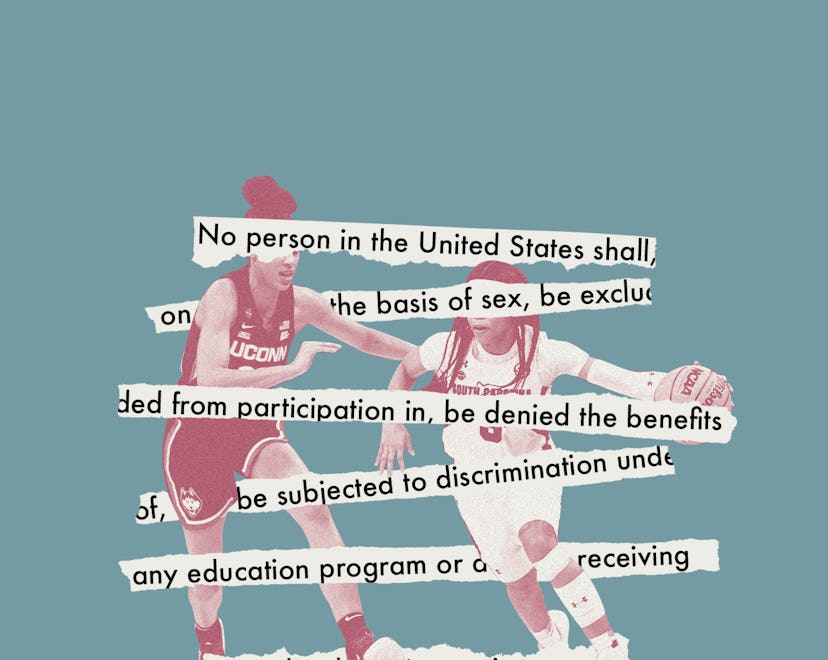

Who Run The World

How Title IX Changed The World For Girls

The landmark law meant girls and women could play sports on a broad scale. But true equality is still elusive.

This week marks 50 years since President Richard Nixon signed into law a piece of landmark legislation with a wonky-sounding name: Title IX. The law declared that any educational program or activity receiving federal funding is barred from excluding or discriminating against anyone “on the basis of sex.” This was, put simply, huge.

At the time, colleges and universities regularly rejected female applicants just because they were women. High schools denied girls academic opportunities because officials believed it was more important for boys to receive an education. And athletics? Forget it. Few high schools and even fewer colleges offered girls the chance to play competitive sports. When schools did host women’s teams, the options — and funding — were extremely limited.

In the decades before Title IX, many girls grew up being told that strenuous physical activity and sweat were “unladylike,” and that it could damage their fertility or make their uterus “fall out.”

In the five decades since Title IX was signed on June 23, 1972, the law has exploded all kinds of educational and professional opportunities for girls and women. But it’s become best known for being the spark that ignited women’s sports in this country and birthed generations of athletes, offering millions of girls and women benefits that boys and men have long enjoyed — from life lessons learned through team sports to a profound feeling of physical strength and confidence.

Historians describe the law’s national influence as nothing short of revolutionary, and no wonder: In 1971, fewer than 300,000 girls played varsity high school sports. Today, that number is nearly 3.5 million. “We gave girls and women the tools of self-determination through sports, and as we did, we rewrote gender rules and gender codes,” says Elizabeth Sharrow, an associate professor of history and political science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who is writing a book about Title IX.

So how did Title IX lead to this massive social and cultural shift — and where has it fallen woefully short?

The way we were when Title IX was passed

In the decades before Title IX was passed, many girls and women grew up being told by parents and authority figures not only that strenuous physical activity and sweat were “unladylike,” but also that it could damage their fertility or even make their uterus “fall out.” For much of the 20th century, women were also discouraged from competing against each other, or even acknowledging an inner competitive spirit, as competition was seen as a conventionally male trait that was unbecoming of a woman.

“The fear was that sport or being competitive would masculinize women, or sort of convolute the role they were expected to play in society as mothers and nurturing figures,” says Anne Blaschke, an associate lecturer in American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston, who is also writing a history of Title IX. “There was also a very strong fear that sport would somehow affect the sexual identity or gender identity of women.”

We now know that sports offer girls (and boys) a host of physical and psychological benefits, including higher levels of confidence and self-esteem and lower levels of depression than girls who don’t play sports. But before Title IX, out of supposed concern for women’s well-being, road races longer than 2 miles banned women from competing, and women who wanted to play basketball were forced to use only half the court, as the full court would be too taxing.

For all of these reasons, in 1971, a paltry 1% of college athletic budgets went to women’s sports, and male athletes outnumbered female athletes in high school 12.5 to 1. Many school officials believed girls and women simply weren’t as interested as the boys in playing sports.

They were about to learn how wrong they were.

1972: When everything changed

In today’s polarized political climate, the notion that Congress once came together to pass truly meaningful legislation may seem mind-boggling. But even in 1972, it wasn’t quite that simple. Inspired by the fight for Black civil rights in the 1960s, a small group of feminist lawmakers stealthily tacked the bill that became Title IX onto the end of a much bigger piece of educational legislation aimed at school bussing and desegregation. They kept the language brief, and they stayed quiet about it.

“Sex discrimination was not foremost on the minds of most lawmakers,” says Sharrow. “But [the architects of Title IX] knew that the problems were manifest.”

Eventually, of course, the overwhelmingly white male Congress did learn about Title IX’s existence, and it set off a fierce debate, but it ultimately survived intact.

In the years following the law’s passage, lawmakers and government agencies hashed out its specific terms and provisions. Finally, in the second half of the 1970s, federal officials began to signal that they would enforce it, warning schools that failure to comply would lead them to yank their funding.

Schools were told that, in order to comply, they must meet at least one of three requirements: They had to offer men and women roughly equal opportunities to play sports, show a history of improving opportunities for girls and women, or demonstrate that they were meeting the demands and interests of their female students.

In 1971, fewer than 300,000 girls played varsity high school sports. Today, that number is nearly 3.5 million.

“Schools could spend more on boys’ sports than on the girls’ sports, but girls had to have a chance to play,” explained the writer Karen Blumenthal in Let Me Play: The Story of Title IX. “The actual money spent on males and females wouldn’t matter — except in scholarship money. If women were about half the athletes, then they should get about half the athletic scholarship money.”

School athletic departments protested, arguing that the law would decimate the men’s sports programs, all for opportunities they assumed few women even wanted. And yet, “Once the barriers were removed for girls, they came out in droves,” says Neena Chaudhry, general counsel and senior advisor for education at the National Women’s Law Center.

By the end of the 1970s, budgets for girls’ sports were tripling, wrote Blumenthal, though they were still “a fraction of what was spent on boys’ sports.”

Proud to play like a girl

In the decades that followed, despite repeated legal challenges, Title IX transformed American culture and academic life. Before the law, only 1 in 27 girls played sports; today, that number is 2 in 5.

“It’s been incredibly expansive,” says Blaschke. “It’s changed our vision of what an active girl or woman has the potential to be, and it has enabled women and girls — as well as trans people and non-binary people — to unapologetically and aggressively and assertively expect the right to play and the right to be competitive and to win.”

By increasing the literal training grounds for women athletes, Title IX has led to steady growth of female Olympians. In 1972, of the 400 athletes representing the U.S. in the Summer Games in Munich, 84 were women. Meanwhile, at the 2021 summer Olympics in Tokyo, women outnumbered men on Team USA for the third straight Games, with 329 women competing versus 284 men.

Title IX has also given rise to women’s professional sports and increased the opportunities for women to get paid to play. “Before Title IX, there was very little opportunity for women to play professional sport,” says Blaschke. “It’s really after Title IX that structures are put in place for women to be paid anything at all.” In the mid-1980s, as the daughters of Title IX came of age, the U.S. saw the birth of the Women’s National Soccer Team. In 1996, the WNBA was launched.

Perhaps most meaningfully, Title IX has helped to bust the sexist myth that women are weak, fragile, and physically inferior to men.

But the mission isn’t accomplished, yet

The passage of Title IX has undeniably led to exponential growth in women’s athletics, but the playing field is still far from even, due, in part, to a lack of enforcement. In the law’s 50 years on the books, “no school has ever lost its Title IX funding writ large despite flagrant, numerous violations all across the country,” says Blaschke. And this, she says, is a “major problem.”

At the high school and college level, girls have more than 1 million fewer opportunities than boys to play sports, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation. “And when they do have a chance to play sports, women and girls often receive worse facilities, uniforms, and equipment; inexperienced coaches; and less support and publicity from their schools — all of which send the message that they are ‘less than’ their male peers,” according to a 2022 report from the National Women’s Law Center.

“It isn't just about the raw numbers. It’s about what is being communicated about the value of spaces reserved for girls and women,” says Sharrow. “We need to think carefully about what it means if ‘equity’ looks like women accepting less all the time and calling it even.”

As women’s collegiate sports have increased in profile and funding, women’s coaching and administrative positions have become more appealing to men — and as a result, the proportion of women in leadership over women's sports has actually decreased since the passage of Title IX.

There is also a striking racial gap in women’s high school and college sports. While 30% of all college athletes are white women, only 14% of all college athletes are BIPOC women, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation.

We need to think carefully about what it means if ‘equity’ looks like women accepting less all the time and calling it even.

But the most visible of the battles over Title IX today may be the fight to allow trans girls and women to play on girls’ and women’s teams, opportunities that a growing number of states are denying trans youth. “When we say to kids, ‘If you come out as gender diverse, you have to give up [all of the benefits sports can bring],’ we are doing extraordinary damage to human dignity, and our society,” says Sharrow.

And so, 50 years on, the success of Title IX may be subjective, says Sharrow. “I think where we are depends on where you sit as an athlete. If you're a trans athlete who's trying to find a place to compete, [things] look a lot different than if you are a normatively-gendered white girl from an upper-middle-class home who blends into these teams and doesn't stick out.”

Title IX has leveled the playing field for some. But far from all.

Want to teach your kids about Title IX?

- ESPN’s new four-part docuseries 37 Words premieres on June 21 and offers a fascinating look at Title IX’s past, present, and future. (Note that the series discusses sexual assault.)

- The award-winning YA book Let Me Play: The Story of Title IX by Karen Blumenthal provides an engrossing, inspiring, and meticulously researched history.

Danielle Friedman is an award-winning journalist who focuses on the intersection of health, sexuality, and culture. Her first book, Let’s Get Physical: How Women Discovered Exercise and Reshaped the World, came out in early 2022. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, New York Magazine’s The Cut, Vogue, Glamour, Harper's Bazaar, the Washington Post, NBC News, InStyle, The Daily Beast, Health, and other publications.

This article was originally published on