Life

Breastfeeding Helped Me Cope With My PPD

I used to say I would never breastfeed. I thought it made your boobs saggy, and the thought of a baby latching onto my nipple just grossed me out. Even while I was pregnant, after I'd heard that breast was best and I'd resolved myself to do it, I had second thoughts.

“Does it feel weird?” I asked my friend Mae, the only person I knew who’d ever nursed. “It feels like nursing,” she said, which was supremely unhelpful and did nothing to allay my fears.

Once my colostrum came in at around 20 weeks, however I was gung-ho about breastfeeding. I would nurse this baby. I would be good at nursing this baby. Little did I know that nursing wouldn’t only be good for him, but it would be good for me as well, because nursing my son helped me recover from my postpartum depression.

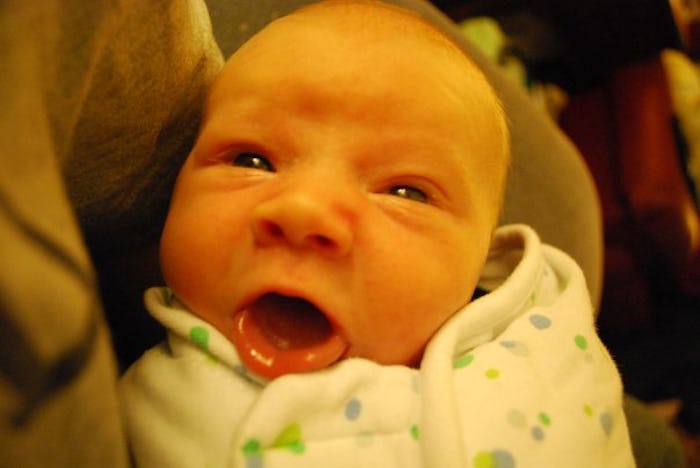

My son Blaise popped out after a protracted labor. After he was born, he lay quietly on my chest and I did what I’d seen in countless nursing videos: I cupped my nipple and brushed it against his lips. He latched on immediately and nursed for about an hour. It had been a terrible labor and delivery: three days of labor had led to my being transferred from a birth center to a hospital. I'd pushed for three hours, which had culminated in my developing a giant, star-shaped tear. But Blaise nursing made it all better. I held him and he sucked and all felt right with the world.

My PPD began to kick in about a week after he was born. I had locked myself in the bathroom. I slid to the floor and wept hard, ugly-crying loudly. What had I done? Why had I thought having a baby was a good idea?, I thought. I’d ruined my life. I would never go out again. I would never do half the things I loved again, because I had a baby in tow. I’d ruined everything.

Then my husband knocked on the door. He said Blaise was crying, and that nothing would calm Blaise down. Could I please come out and nurse him? So I wiped my tears, went out to the couch, and found my Boppy pillow. Blaise latched on and suddenly, everything was OK again.

The only things that helped me feel better were wearing him in a Moby wrap and nursing him. These were two things I could do. These were two things I was good at, two things only I could do well. They became a kind of tether to the world.

My PPD didn’t get much better. In fact, it only got worse. I didn’t find myself weeping in bathrooms so much, but I lived in a sort of gray fog of misery. I ate. I slept. I took care of the baby. The only things that helped me feel better were wearing him in a Moby wrap and nursing him. These were two things I could do. These were two things I was good at, two things only I could do well. They became a kind of tether to the world.

It didn’t help that we think Blaise later developed severe reflux and milk/soy protein intolerance (MSPI). He wasn’t a pretty baby. His cradle cap scaled down over his face and onto his body. His poop was green and full of mucus, and he screamed after he ate. He screamed, in fact, while he ate: I used to count the sucks between the cries and beg him to nurse more. But I knew that nursing was the best thing for him.

I considered not nursing Blaise a few times. Every once in a while, he cried so hard he choked, and I thought formula might be a better choice for him. But then we heard about MSPI. Although we never confirmed the diagnosis with our pediatrician, it was clear from his symptoms — cradle cap, severe diaper rash, green poop, etc. — that something was wrong, and in a way, it saved me.

There was nothing like being needed to jolt me out of my fog. I had to feed the baby. So I did.

I had to go off all milk and soy - not just the obvious yogurt and butter, but all trace amounts of dairy and soy. Only I could nurse him. Only I could feed him without him getting sick, unless we shelled out for super-expensive prescription formula. So it was up to me to feed Blaise. He depended solely on me for sustenance. There was nothing like being needed to jolt me out of my fog. I had to feed the baby. So I did.

The feel-good hormones produced by breastfeeding, such as prolactin and oxytocin, helped me, too. Oxytocin and prolactin work together to help the mother-child bond and establish a warm, contented state. That certainly happened in my case. I never felt as capable of a mother as I did when I nursed my son. I might have been depressed, but when I was curled on the couch, nursing my son, I felt empowered. I could feed a baby from my own body. I was powerful. I was maternal. I had this motherhood thing under control.

My PPD got better once my medication was adjusted. I went from the lowest dose of Zoloft to a higher one, and in a week or two, I felt much more like myself: more capable, stronger, and better as a mother. The fog lifted. But until that happened, nursing was my anchor. I felt needed. No one could do the job I was doing, so I had to put my own misery aside and do it.

Back then, I cried a lot. But I never cried when I was nursing the baby. If we had formula fed, I don’t think I would have felt as needed, and I think that, due to my depression, I wouldn’t have bonded as well with my son. Nursing might have kept my son fed. But it ended up saving my life as well.