Life

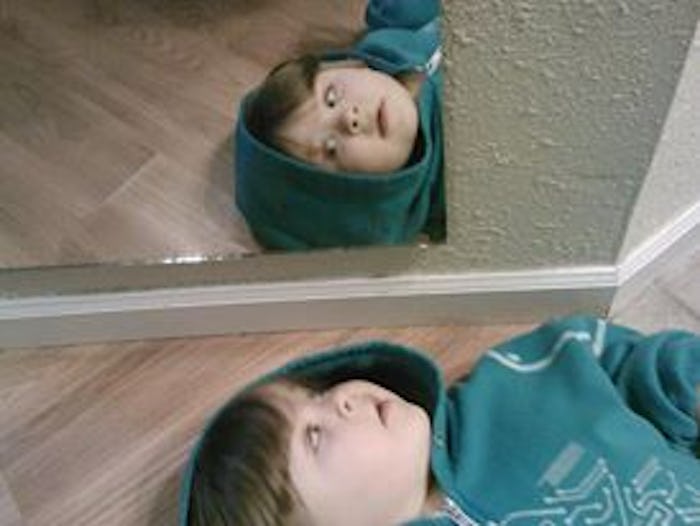

I’m Raising A Child With Social Anxiety, And This Is What It’s Really Like

When Arthur was three-and-a-half-years old, his preschool teachers brought us in for a conference. One of them left a message on my phone telling me she had concerns about Arthur's development but that I shouldn’t be worried, which of course worried me even more. I spent the next few days leading up to the conference scouring the internet for typical three-year-old developmental progressions.

"What were his teachers seeing that I wasn’t?," I asked myself. "What was happening?"

When I went into the meeting with Arthur’s preschool teachers, I couldn't stop wondering what they were going to say. When they told me they were worried he had a speech issue. I laughed.

“Oh, no. He doesn’t," I said.

“He doesn’t talk in class," his teachers said.

“What?”

“He doesn’t talk in class or in group.”

I turned to Arthur. “Kiddo, you don’t talk at school?," I asked.

Then Arthur started talking, his little arms wrapped around me. He talked about how he didn’t know the kids and didn’t know what to say around them.

“That’s the most I’ve ever heard him say,” said one of the teachers.

Arthur wandered off to play with toys, occasionally coming by to play with me and his dad and his mom. (There are three of us parenting him. I am genderqueer, and he calls me his Baba. He calls my partner, who is a cisgender woman, his mom, and he calls my other partner, who is a cisgender man, his dad.) Together, we realized that Arthur didn't have a speech problem — he had social anxiety, which was making him afraid to speak up in class.

I wasn't surprised to hear that Arthur was struggling with anxiety, because I too have generalized anxiety disorder. It is a fairly severe case; I take daily medication for it, and I’ve been in and out of therapy over the years to develop coping strategies to manage it. My anxiety manifests in ways that make me appear high-functioning until they break down.

Because I was so high-functioning, it took a long time for my anxiety disorder to be diagnosed. When it finally was, everything snapped into place. It was mind-boggling to realize that my brain was broken in some very specific, very real ways, that other people's brains were not.

Gentle social interventions from the teachers helped Arthur with his social anxiety. But now that I have seen the strain of anxiety in him, I can’t unsee it. I know he has a brain like mine. I can see it spinning sometimes. He worries a lot. He is hard on himself when he fails or gets in trouble. He doesn’t always bounce back like other kids do. He gets scared that I will stop loving him — and when I ask him why that scares him, he looks at me, his face full of tears, and says it’s because it’s the scariest thing. And that’s the heart of anxiety: never being able to stop thinking about the scariest thing that can happen.

He gets scared that I will stop loving him — and when I ask him why he is scared of it, he looks at me, his face full of tears, and says it’s because it’s the scariest thing. And that’s the heart of anxiety: never being able to stop thinking about the scariest thing.

I talk to Arthur a lot about how my brain works. I tell him when I am scared, and what I get scared about, and how I make myself feel less scared. Already, at five years old, he has had panic attacks. I’ve taught him my coping strategies for panic — breathing, meditation, the importance of cataloguing how he feels physically, and making sure he is eating and sleeping enough to keep panic attacks from happening.

It's hard knowing that Arthur struggles. It's also hard to talk about these issues with a five-year-old, simply because five-year-olds don’t always have the self-awareness to tell you what really frightens him. Sometimes the anxiety washes over him so fast that he just drowns in it, weeping hysterically, and he can’t tell me why. By the time I've calmed him down, he has forgotten what the trigger was.

I'm trying to give Arthur what I wish I had growing up. I’m trying to give him the language to describe what anxiety is at a young age, so he can name it and know it. I’m trying to show him that it’s OK to grapple with mental health issues. Those of us who do need tools to manage them, and we need help, sometimes, from the people who love and care about us. I’m trying to give him the tools that have worked for me, and trying to help him find the tools that work for him.

I’m trying to help Arthur make peace with the fact that his brain will never let him unsee the scariness of life. It will always be right there, salient, looming. For some of us, the world is hard to navigate, but I hope that showing him how I do it makes it easier for him to navigate it himself.

This article was originally published on