Life

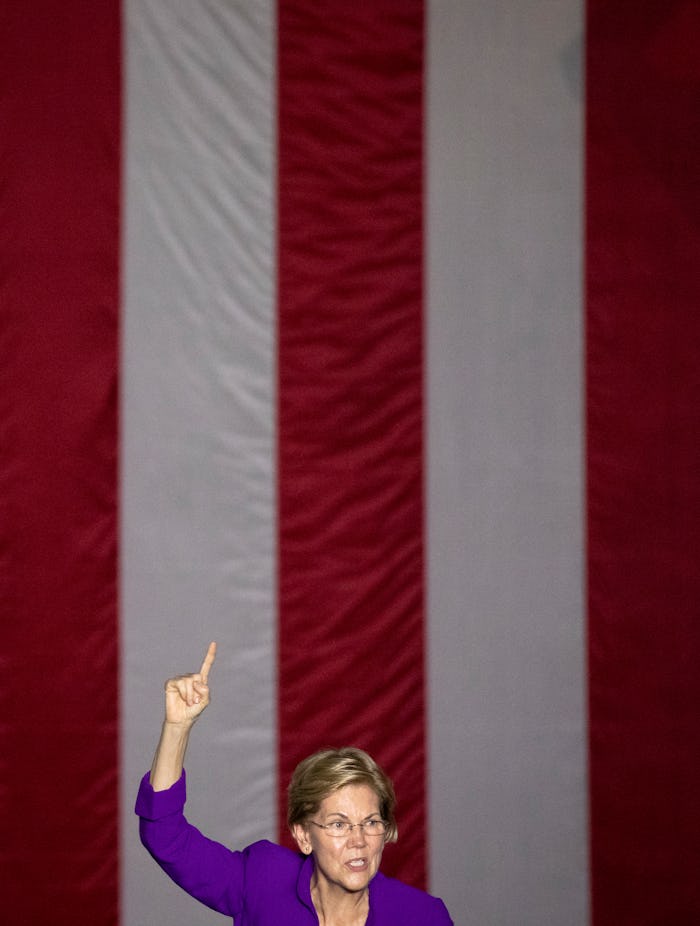

Elizabeth Warren Is Coming To Save Working Moms

“I could do hard, but the part that brought me to my knees was child care,” says Senator Elizabeth Warren of her time as a working mother of two small children.

“In the space of just a few months we went through the day care center, the babysitter who didn’t show up, then back to a different day care center, then they closed and another one moved and another one smelled funny and another babysitter flaked out on us,” Warren explains to Romper after speaking at a NARAL Presidential Town Hall in New York City on September 17. “And it was in the early spring when my Aunt Bee called me — she was my widowed aunt from Oklahoma — and she said, ‘How you doing hun?' and I said, ‘Fiiiiiiiine.’"

Like so many parents who are “fiiiine,” she couldn’t keep herself from crying at that point. “I said, 'I’m going to quit my job. I cannot do this. I am failing my family. I am failing work. I’m just failing as a person.' And I cried and I cried.”

Aunt Bee waited for Warren to finish, then gave her the lifeline she didn’t know she needed.

“She said, ‘Well, I can’t get there tomorrow. But I can come on Thursday,’” recalls the presidential candidate. “And she arrived with seven suitcases and a pekingese named Buddy, and stayed for 16 years.”

In February, Warren introduced her Universal Child Care and Early Learning Program proposal, which would fund universal child care for children ages 0 to 5, universal pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds, and raise the wages of every child care worker and preschool teacher in this country via a $0.2 wealth tax on the top 0.1% of Americans.

She said, ‘Well, I can’t get there tomorrow. But I can come on Thursday.’

Her proposal seeks to address a pain point for millions of Americans. The average American family spends 10% of their income on child care, per child, a year, according to Child Care Aware of America’s 12th Annual Cost of Care report. An estimated 2 million parents sacrificed their careers as a result of inadequate or out of reach child care, according to a 2017 report from American Progress, and families that earn less than $100,000 a year cite cost as the main reason why they cannot access child care.

Warren knows the statistics backwards, but for her, it is personal. The senator was born into a middle-class family that slipped to working class after her father’s heart attack bankrupted them. She worked as a public school teacher for students with disabilities after graduating with a degree in speech pathology and audiology, but after her first year, visibly pregnant with her daughter, Amelia, she wasn't asked to return, as she explained in the September 12 Democratic debate. A new mom at 24, she instead attended law school and eventually worked her way up to tenured professor, lecturer at Harvard Law School, and, in 2012, senator for Massachusetts. Her rise occurred alongside and through raising a family.

“I was working my rear-end off, and really slipping here and there a lot,” Warren recalls. “Dinner was late, I was doing laundry at 10 o’clock at night, and doing my class preparations for the next day at midnight.” Warrens says it was hard, the way parenting, regardless of your circumstances, can be hard.

“I think about how many mammas, and daddies, get bumped off the track, aren’t able to finish their education, aren’t able to take the full-time job, aren’t able to take the more challenging job, all because of child care,” Warren says.

What they need, she argues, is a lifeline. “I’m here today because my Aunt Bee saved me and my family,” Warren says. “And if everybody in America had an Aunt Bee, we would be doing just fine. But they don’t.”

Warren believes young families face child care burdens that are exponentially worse than they were two generations ago; worse than when she was crying on the phone to her aunt, telling her she believed her only option was to quit her job.

If everybody in America had an Aunt Bee, we would be doing just fine. But they don’t.

But she has a plan for that. It’s not a plan that she can hand over to the American people tomorrow, but she’s hoping that, by 2020, and like her Aunt Bee did for her, Warren will show up for families who feel like they’re failing their children, their jobs, and themselves.

“We need to invest in our babies because it also means we’ll be investing in their mamas and their daddies,” Warren says. “We’re going to do this. We can make this better. You and your children are worth investing in.”