News

What The New Internet Privacy Rule Means For Parents

Both the Senate and the House have voted to use the Congressional Review Act to repeal a recent broadband privacy rule, and it's expected to be signed into law by President Donald Trump. There's a lot of confusion over what the old rules were, and what the new ones will be. If your kids use the computer, you might wonder what the internet privacy rule means for parents, and whether your kids' private information is now for sale. The short answer: they're safer than adults, but it's still dicey.

House Joint Resolution 86 passed on Thursday, less than a week after Senate Joint Resolution 34. The pair of measures nullified a 2016 Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rule called Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services, which essentially gave the FCC the authority to regulate internet service providers. It might seem like a no-brainer that the internet would fall under the FCC's jurisdiction of "communications by radio, television, wire, satellite and cable," but until recently, it did not. Previously, internet service providers – the companies that consumers pay to hook up to the internet, such as Verizon or Comcast – were governed by the Federal Trade Commission, and some trade organizations argue that should be good enough. The 2016 rule stated that the Communications Act of 1934 should be applied to internet service, requiring providers to allow consumers to opt-out of personally identifiable information tracking for advertising purposes.

Industry reps claimed that internet service providers are being "unfairly targeted," according to New York Magazine, because companies like Google and Facebook aren't subjected to the same rules. But the use of sites like Google and Facebook is optional; many consumers don't have a choice of internet service providers, meaning if they object to a provider's policy, they can't access the internet at all. And while individual websites only have access to data collected on their sites, service providers have access to everything.

So does that mean consumers will soon be subjected to billboards addressing them by name? Probably not. U.S. Code Title 47, Section 222 requires that carriers obtain "express prior authorization" before collecting personal information. But there are two problems with that: first, the law was technically written only for "telegraphs, telephones, and radiotelegraphs," so a lawyer might be able to argue that it doesn't apply to the internet. Second, "express prior authorization" simply means checking "I agree" on a privacy notice, and nobody reads those.

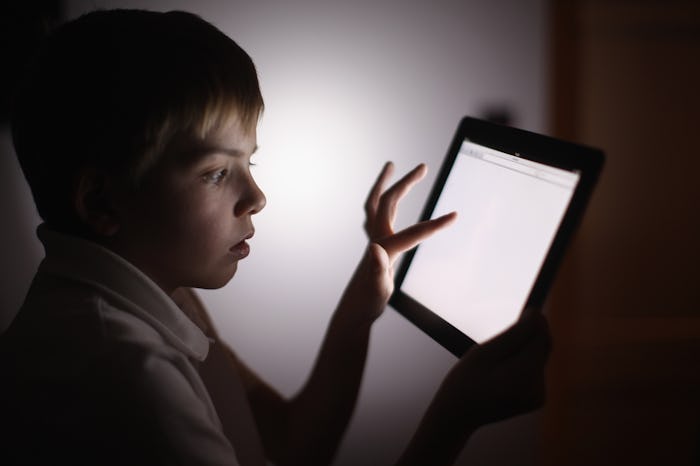

Kids are a little safer online, however. The FTC does have a special law in place for them: the Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule, or COPPA. COPPA requires that sites which are "directed to children" must make a "reasonable effort" to determine whether a user is a child under 13, and obtain authorization from a parent before collecting kids' personal information. Still, a "reasonable effort" isn't an exhaustive effort, and providers are only penalized if they have "actual knowledge" that a user is a child, so there's a lot of gray area. The best practice is to closely monitor kids' internet usage, and teach them to treat corporations and websites the same way they would individuals: don't volunteer any personal information, ever.

But kids aren't the only source of information about themselves. Even if a parent is careful not to overshare about their child on social media, service providers could theoretically gather information about children by monitoring parents' activity. Browsing parenting websites, researching preschools, scheduling pediatrician appointments or shopping for toys online all paint a very specific picture of a child; parents' internet history could easily reveal sensitive data about their kids, including where they live, and what medical conditions they might have. Parents should familiarize themselves with their providers' current privacy policy — the one they probably signed without reading — and opt out of data collection if applicable. If and when the policy changes, providers will have to issue an update, so make sure to read that in full, as well. If you still don't trust your provider, you can always create a virtual private network or just move into a cave and live off the grid.