Life

When Will There Be A Zika Vaccine? The World Is Stepping Up To Combat The Outbreak

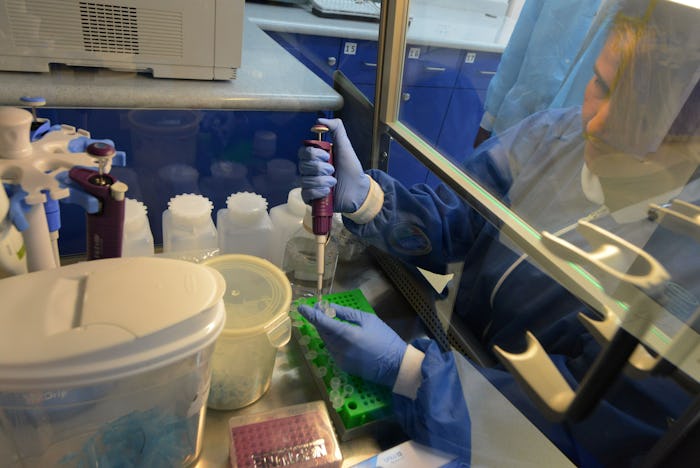

The White House on Monday reported that President Obama would be asking Congress for $1.8 billion to provide mosquito control programs to the public, improve health care for low-income pregnant women, and step up research for a Zika vaccine to combat the recent outbreak that's been plaguing the Americas in full force. While mosquito control and health care are actionable, immediate, and measurable steps to be taking to help control Zika virus, a vaccine is somewhat trickier. That's not to say that research isn't desperately needed, because it is. But it may take longer to see results than we'd like, and no one can definitely say when there will be a Zika vaccine.

Vaccine development is no easy task. Take, for example, dengue. A mosquito-transmitted virus similar to Zika, it only had its first vaccine approved in December — and it was a vaccine that took 20 years to create. While dengue isn't linked to Guillian-Barré syndrome or microcephaly, the two conditions that have been associated with Zika, it's still responsible for half a million hospitalizations a year, and the World Health Organization has reported explosive outbreaks across the 100 countries dengue is endemic to. It's not that there wasn't a want for a vaccine — it's that creating a safe, effective vaccine is time-consuming and expensive at the best of times, a process which isn't helped when doctors are up against dengue, which dengue expert Dr. Scott Halsted called "the most amazing perversion of the immune response," during a 2009 interview at the New York Academy of Sciences.

Not all vaccines take such a convoluted route to success, however. The Ebola crisis led to a race for a vaccine, and in some regards, one could consider it a success. When the crisis began in Dec. 2013 in Guinea, the world had no treatment or vaccines to combat it with, but a vaccine trial in Guinea in Jul. 2015 saw promising results. By then, however, an estimated 11,000 people had already died, according to CNN, and, as outbreaks have waned, only small sample sizes were available to determine efficacy.

Now, the race is on to find a vaccine for Zika. One problem researchers are up against is simply a lack of knowledge. "We know very little about the biology of this virus," Nicholas Jackson, the Global Head of Research at Sanofi Pasteur, told CNN. Even during the virus' first human outbreak in 2007, it seemed relatively benign, only presenting symptoms in a fifth of cases and seeming fairly mild, so there was no real need for a vaccine. Now that it's being tied to Zika and Guillian-Barré syndrome, however, its threat has exponentially increased.

Jackson and the rest of the Sanofi Pasteur team, whose dengue vaccine was approved last year, hope that the two diseases' similarities will help them find a Zika cure. Protein Sciences, an American pharmaceutical company, claimed that it could potentially begin human trials in as little as two months, but cautioned that the clinical process could take three to five years.

The American government is taking a two-pronged approach to finding a Zika vaccine as well, but National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony Fauci said the vaccine would be "unlikely to be widely available for a few years", according to Reuters.

Even if vaccines are still a few years out, the funding Obama is requesting could go a long way to combating Zika. Out of the requested $1.8 billion, $250 million would go directly to Medicaid efforts to help those affected in Puerto Rico, and another $335 million would be used to assist countries being hit the hardest, according to ABC. While a rush to find a vaccine is definitely useful, combatting the Zika outbreak in the next year or so will realistically be relying much more on mosquito control, expedited care for pregnant women in affected areas, and — just maybe — a change in reproductive laws and more liberal family planning.