Parenting

Harry Styles Is Here To Remind Parents & Kids That Clothes Have No Gender

It's pretty simple.

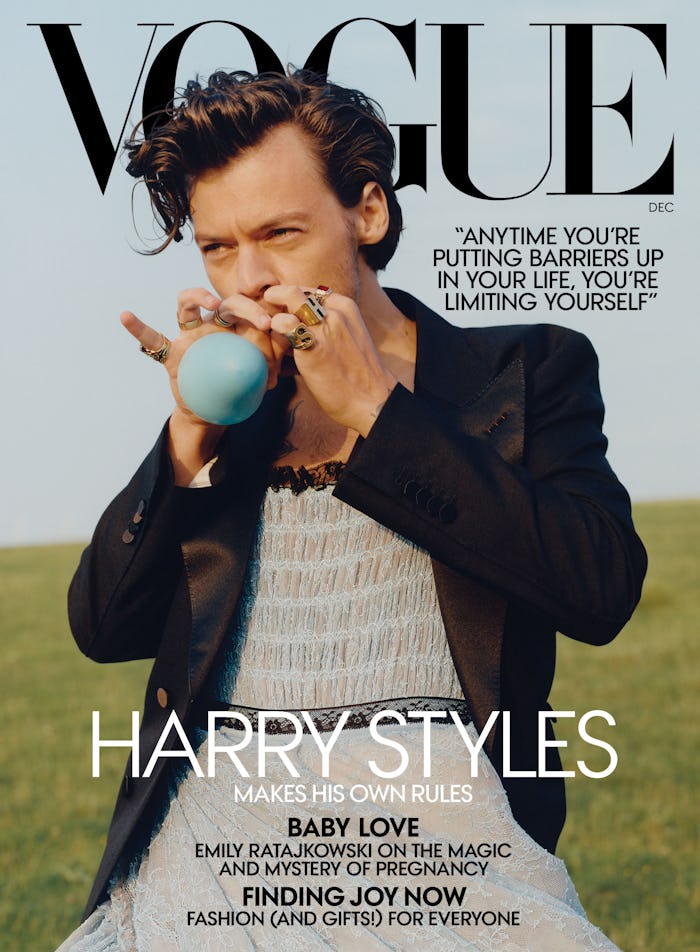

Harry Styles made news this week as the first man on the cover of Vogue. The fact that he did so in a ruched lace gown beneath a black Gucci jacket caused prominent right wing critics to declare that we need to bring back “manly men.” They called Styles’ choices — Braveheart-esque kilts; houndstooth and plaid; slouchy socks; and a trench coat/butterfly wing concoction that would fit in at the Met Gala — an “outright attack.”

A chorus of fashion lovers and liberal commentators jumped to his defense: Styles looks fantastic in clothes we'd expect to find in the "women's" section, and good on him for bending the gender rules, they said. He showed dress-loving boys everywhere that their inclinations and interests were well within the range of normal.

As the parent of a daughter who hasn’t worn “girls’ clothes” since she was 4 years old, and the author of a book about gender nonconformity, I think Styles is doing even more than that. He’s reminding us that those gender rules are arbitrary, restrictive and outdated.

He’s also presenting parents, especially parents of sons, with an opportunity to understand the bleak history behind the idea of “boys’ clothes” and “girls’ clothes” and why we don’t need to perpetuate the same misguided beliefs.

Up until about a hundred years ago, most young boys and girls dressed the same way. Babies of both sexes wore white dresses. Until they went to school, around age 6, most boys and girls grew their hair long and wore dresses of other colors, embellished with lace and flowers, according to Jo. B. Paoletti’s Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America. Children were dressed according to age, not sex.

Up until that time, most westerners conceived of sex, gender and sexuality as one intertwined thing. That is, in the zeitgeist of the time, your male or female sex determined your gender — how you should look and behave — and your sexuality. To ponder a child’s biological sex conjured images of that child as a later sexual being, something nobody wanted. Adults didn’t concentrate on boys and girls as fundamentally different creatures until they were a bit older and needed to be prepared for their separate spheres: girls as subservient and domestically-oriented, boys as dominant and job-orientated.

I have heard from dozens of parents whose sons love dresses, pink, sparkles and whatever version of a trench coat/butterfly wing concoction they have on hand, and most of those parents are in distress.

But around the turn of the 20th century, the fields of psychology and sexology — the study of human sexuality — expanded, and experts began contemplate differences in sexuality and to to believe that nurture, not nature, made people gay. Early child psychologists suggested to parents that they begin to dress children as young men and young women to encourage them to inhabit — literally and figuratively — their gender roles early, to prepare them to become proper heterosexual adults.

Anything “feminine” and delicate and beautiful—lace and frills and flowers—was stripped from boys’ clothes, replaced with balls or manly animals like bears or lions. Toys followed a similar path, with more erector sets for boys and mops and brooms for girls, with explicit messages about how these toys would help groom them to walk their gendered paths.

In short: the gendering of kids’ material worlds is rooted in homophobia and misogyny, designed for kids to internalize the message that their sex determines how they should behave and dress, how “masculine” or “feminine” they should be, and whom they should be attracted to.

I have heard from dozens of parents whose sons love dresses, pink, sparkles and whatever version of a trench coat/butterfly wing concoction they have on hand, and most of those parents are in distress. Either they fear, rightfully, that their sons will be bullied, or they think there is something fundamentally wrong about a boy liking what is supposed to be for a girl.

When my own daughter started asking for short hair, sweatpants and t-shirts, I, too, was taken aback, even though I grew up in the '70s and '80s, when girls and boys often had matching bowl haircuts and identical striped t-shirts and corduroys. I failed to ask myself why I thought her inclinations, including playing with boys, or looking a certain way, belonged only to boys. I forgot to ask where my idea of what’s normal for boys or girls came from, and once I did, the answer shocked me.

But it also gave me permission to stop participating in this ridiculous pink/blue division. No clothes, toys, people or activities will be off limits to my kids because of their bodies. Knowing the history reminded me, as Styles does, that clothes have only the gender we assign to them. No inanimate object is inherently masculine or feminine. No child’s genitals need determine what they can access, or dress up in, or play with.

When children are very young, they don’t understand the difference between gender stereotypes and biological sex. They believe that, because dresses are for girls, putting one on a dress will make them a girl. Apparently, some adult members of the right wing believe this, too — hence how deeply uncomfortable Styles’ photos made them. Or maybe the problem, as some have said, is just that some men are envious of how good Styles looks in skirts and dresses.

As kids get older, starting around age 6, which is when, even eons ago, they were expected to start performing gender, they begin to understand gender constancy. They understand that their sex doesn’t change based on how they present themselves to the world. At this stage, many girls begin to reject dresses in favor of pants. But boys don’t go through a similar stage; they don’t feel freer to experiment or transcend gender boundaries. Boys learn early and often that the rules around their gender are impossibly strict.

He’s offering parents of dress-loving boys — and even boys who reject dresses — a role model, with the imprimatur of the world’s most important fashion magazine.

And yet so many parents are recognizing the need to open up what’s marketed to girls as boy-friendly, too. There are new brands that sell “feminine clothes” to boys, or use boys in dresses in their catalogs and marketing materials. Styles isn’t so much creating a new normal so much as shedding light on a hidden one that already exists.

Styles says in his Vogue interview that he has always loved to play dress-up, and he joins a long line of gender-bending performers, from Patti Smith to David Bowie to Prince, who grabbed from both sides of the pink/blue divide.

But Styles’ images appear amid a national discussion of toxic masculinity, and of how boys are taught to tamp down their human impulses and desires. He’s offering parents of dress-loving boys — and even boys who reject dresses — a role model, with the imprimatur of the world’s most important fashion magazine.

He’s showing them how one can be celebrated for crossing or ignoring the lines that rule so much of childhood. And in doing so, he’s showing some children — and adults — what’s possible.

Lisa Selin Davis is the author of TOMBOY: The Surprising History and Future of Girls Who Dare to Be Different. She has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Time, Salon, The Guardian, and many other publications, and is the author of two novels.

This article was originally published on