Kid Behavior

The Pros & Cons Of Using A Reward Chart

What's the harm in handing out prizes for good behavior? That all depends on whom you ask. But there may be more at stake than just stickers.

How many times have you stared down at the floor and thought to yourself, “Why can’t they pick up their shoes?” Or maybe you repeatedly pass your little one’s rumpled sheets and wonder, “When will they attempt to make the bed?” Oh, wait, here’s a favorite: “Why can’t you put away your toys before someone trips?” Motivating toddlers can be a frustrating job, so it’s understandable why there are so many tools, tricks, and techniques to help guide their behaviors. The reward chart is a common, if controversial, one.

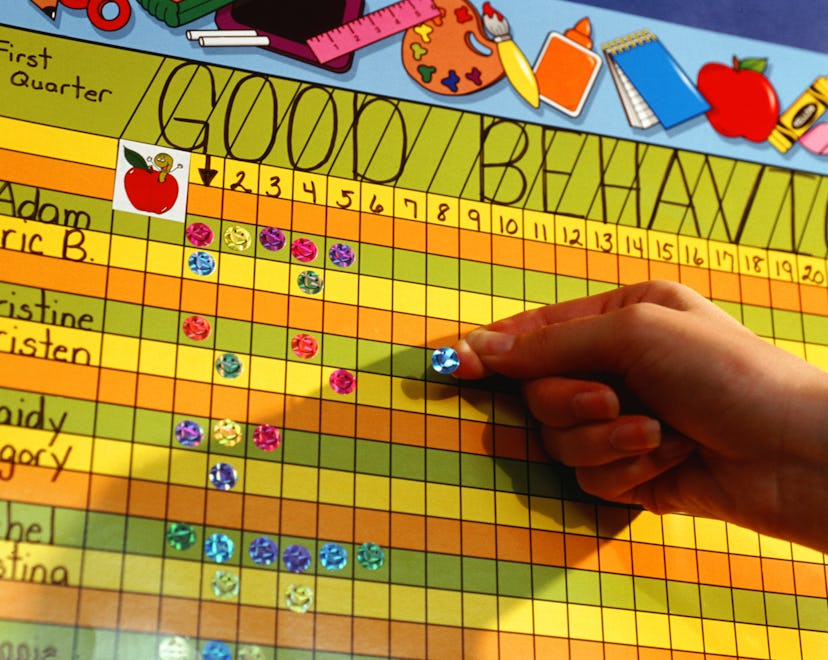

At first thought, the tool seems simple enough: Lay out the behaviors you want to see, or tasks you want performed, then offer your child a reward for doing each one. This can be a sticker, or, for an older child with a longer attention span, say, a series of stickers that culminates in a prize. Reward charts are accessible, easy to print out or draw yourself, and often fun for kids to interact with. But upon deeper thought and investigation, some people may feel that reward charts may, unintentionally, spark insecurity, embarrassment, or unsustainable expectations. So much for simple, right?

It’s a device that has its supporters and detractors, its believers and its haters. But, as a caregiver, the arguments on all sides are worth an ear. Ultimately, you can be your own judge, and your child can be your guide.

What’s The Possible Harm In Using A Reward Chart?

Well, that depends on whom you ask. Regarding the use of reward charts in a classroom, Rachel Robertson, vice president for education and development at Bright Horizons, told Romper that they may prompt embarrassment or shame in a child. Safe to say that’s never the goal, but there’s something intrinsically evocative, and emotionally indelible, about seeing yourself publicly ranked among your peers — there’s always someone at the top, and at the bottom, of the list. Then again, one could argue, aren’t ranking and rating systems common tools used throughout adulthood?

Certified early childhood teacher and preschool administrator Nicole G. tells Romper, “I am not a fan of rewards charts at all.” Rather than incentivize young children with prizes, or extrinsic motivators, Nicole says, “Instead, I emphasize doing positive actions because they feel good to do, make one proud, and are fun for fun's sake. For example, we don't think playing a game is wasted time if we lose. We see the fun in playing the game to begin with, and we want to try again.”

Having seen reward charts previously used in school classrooms, Nicole tells Romper, “At the end of the week, children would leave crying [because] they hadn't won a toy [or] sticker — and they would never change their behavior.” In the long term, there might be other potential side-effects to consider: “The constant quest for external gratification may lead to perfectionism or a win-at-all-costs attitude,” she says. “Some activities are fun, and some are not. We do them because they are a part of life.”

Is It Ever A Good Idea To Use A Reward Chart?

The concept of the reward chart can hardly be simply summed up as just “good” or “bad.” But before considering bringing one into your home, many experts say there are practices and techniques caregivers can try first when motivating children. One is reinforcing positive behaviors with positive attention, says Mari Kurahashi, M.D., MPH, clinical associate professor, co-section chief, general psychiatry at Stanford School of Medicine. That can be praise offered warmly and enthusiastically, directly after a child performs a task.

“Praise works both consistently and intermittently, but I would caution against [just saying] ‘Good job!’ Be specific with praise, and children will repeat the behavior associated with it,” Nicole says. “For example, [saying], ‘I see how hard you worked at cleaning up your scraps of drawing paper! Would you like to save them for another project or recycle them?’”

Another idea is consciously modeling behaviors for your kids. “Adult caregivers can model chore completion for children and say, ‘Wow, don't you love it when you can find your toys easily? Let's sort them so they stay easy to spot,’” Nicole suggests. “Talk about their feelings, validate them, and mention stories from your own life about things you didn't want to do, but were glad you did.”

Another thing caregivers can keep in mind is how they offer direction for a child to follow, Kurahashi says. For example, if a parent gives their child multi-step commands, depending on their age and temperament, they might not be able to retain all of the information and follow through. “Parents need to remember to give one command at a time. And then reward that followthrough with an acknowledgment.” Even if it’s just a kind, “Oh, thanks for listening right away,” it’ll help to reinforce behavior, Kurahashi says. Caregivers can also help motivate good habits by offering direction in a mindful way — not yelling it from a few rooms away, Kurahashi says. “Another key point in how to give an effective direction is for the parent to wait at least five seconds before repeating themselves.” Otherwise, your child might get used to waiting until they hear a command said multiple times.

Visual aids, that aren’t centered around rewards, can also be helpful. Say you want a child to have a smoother morning routine: Having a chart with pictures of the steps they need to accomplish can boost the chances of getting out the door faster, Kurahashi says.

If all of these things aren’t enough — which, oftentimes they can be — then a reward-based system may help, Kurahashi tells Romper. One very specific short-term goal for which Nicole thinks a reward chart can be beneficial? Toilet training at home. “When a toddler does an appropriate toileting behavior — such as "sitting on the potty" — and is reinforced with a special item that is not otherwise available — tablet time, a fruit gummy, etc. — it has worked.”

Is There A Right Way Or Wrong Way To Use A Reward Chart?

A reward chart works in two ways, says Teresa T. Hsu-Walklet, assistant director, Pediatric Behavioral Health Integration Program (BHIP) at Children's Hospital at Montefiore Medical Center. “It is not only meant to increase the desired behavior, but also to encourage the child to feel proud about succeeding and meeting the goals set in the chart. Therefore, keeping targets simple enough to do, but effortful to complete, is essential.”

Also picking one or two important behaviors to put on the chart at once — and not overloading it with every single task that needs to be done — is good practice. Try to frame them in the positive, not negative. Rather than, “‘Stop being rude,’ a goal might be to remember to say ‘please,’ and ‘thank you,’” Kurahashi says. So the idea is to frame it with the goals or behaviors you want to see, says Hsu-Walklet. Instead of “no hitting,” the goal might be, “keep my hands to myself for X amount of time.”

Now let’s talk rewards. “Charts must be consistently implemented, with rewards given immediately, or the child isn’t tying the behavior with the reward,” Hsu-Walklet tells Romper. So let’s say a child cleans their room; promising a movie later on in the week might not be as successful as offering a fun game or screen-time treat in the present moment. But you want to keep the reward on the small-ish side, so maybe save the new bike for a special occasion. The key takeaways here are to make the behaviors doable, and the rewards immediate, says Kurahashi. “Cause if they never get the reward, they’re going to lose interest right way.”

Hsu-Walklet also offers advice around food: “Rewarding with food, and rewarding eating habits are discouraged.” Those practices might have a negative impact on a child’s beliefs around eating later in life. “Rewarding eating vegetables with ice cream may inadvertently suggest that vegetables are ‘undesirable.’” Hsu-Walklet notes that “mismatched rewards,” like, say, giving a video game if a child clears their plate for a week, might also be problematic, “as it can give an inflated sense of the worth of behaviors.”

When Can I Stop Using My Reward Chart?

If you’re using one, the goal is to phase it out, and there are recommended ways to try. You can amend or update the behavior that’s being rewarded. For example, if the goal was getting dressed every morning, and that’s been getting done successfully for some time, you can start giving maybe a prize after a school-week’s worth of smooth morning routines. This way, “We’re moving forward, [but] it’s not that we’re increasing the rewards, but actually moving forward with our expectations after they’ve shown their ability to do these things more routinely,” Kurahashi says. From there you can eventually fade out the material reward altogether. “Because, in theory, once the behavior is really ingrained — especially those types of behaviors that would be on the reward chart, like the morning routine — once those behaviors just become more regular, then they don’t need as much material reinforcement.”

But no matter into which side of this discussion you lean, it’s important to remember this: No technique is foolproof and 100% guaranteed to work for every child. “Certainly with parenting, nothing is 100%,” Kurahashi says. Instead, gauges success in a reward plan if it has a 70 or 75% success rate. “Children are not robots. [Nothing] we do is going to make them 100% percent compliant — and thank goodness.”

Experts:

Nicole G., certified early childhood teacher and preschool administrator

Mari Kurahashi, M.D., MPH, clinical associate professor, co-section chief, General Psychiatry, co-director, Parenting Center, director, Mindfulness Program, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Stanford School of Medicine

Teresa T. Hsu-Walklet, assistant director, Pediatric Behavioral Health Integration Program (BHIP) at Children's Hospital at Montefiore Medical Center