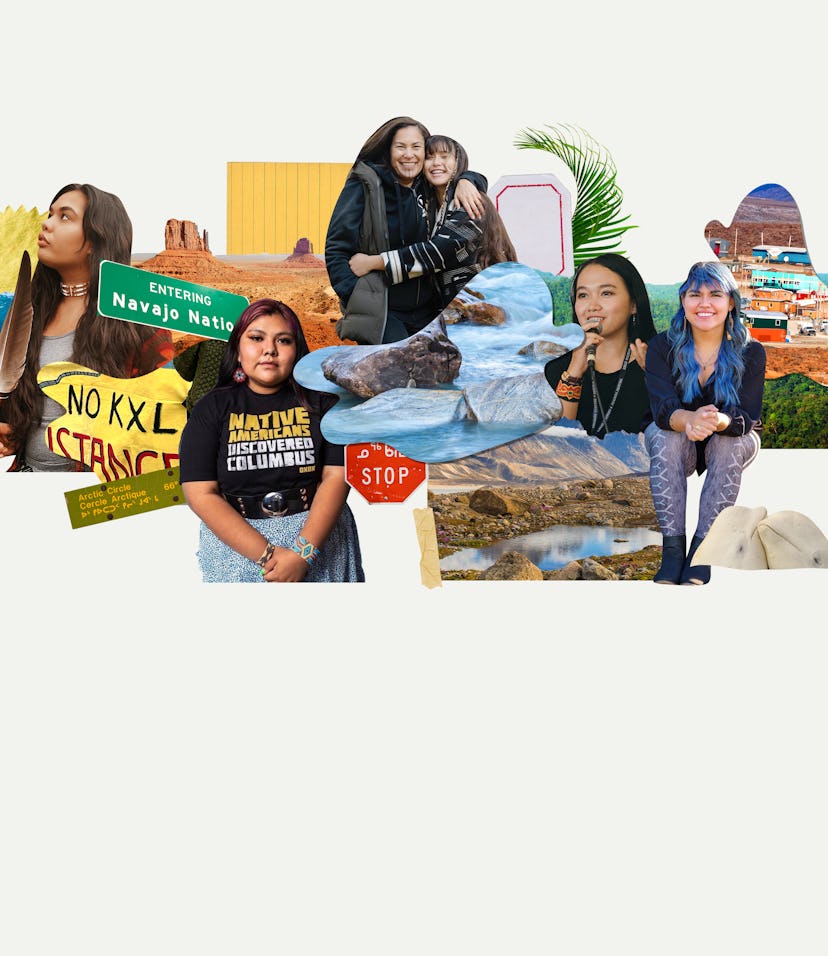

Indigenous Youth Are The Future Of Climate Activism

They know what needs to change, but they need others to stand with them.

I worry often about how I’ll explain climate change to my child. At 2, she is happiest outside, filling her pockets and mine with chestnuts and pinecones. She doesn’t know that the summer sky shouldn’t be choked by wildfire smoke. I want to save her from the despair I feel when I try to grapple with the enormity of our collective crisis.

But maybe she’ll save herself. The five Indigenous youth I spoke to draw strength from many sources — their families, cultures, ancestral territories, communities — but also from within. They understand the challenges but are hopeful for the future. They know what needs to change, but they need others to stand with them. It’s our responsibility to listen to them, and to follow their lead.

I’m from the village of Stella, in unceded Dakelh territory, which is in the north central part of what we now call British Columbia. My people are the Stellat'en, which means people of the cape. All of our places are named for water, and our relationships to water, and I think that really speaks to our responsibilities of protecting that water. I’m also Afro-Indigenous, so I carry the responsibilities of being a Black and Indigenous person.

As a kid I was obsessed with wild salmon. My favorite time of year was watching the salmon run come home. I was amazed at the journey they go through to come back to my home waters and lay their eggs for future generations. So many species all around us instinctually do whatever it takes to ensure the survival of future generations. I believe humans have that too, but it’s something we’ve lost through colonialism.

I did witness a lot of environmental degradation [growing up]. Deforestation, pollution of our waterways, oil and gas activity forced through our territory … now I really see the connection between that extractive activity and the women who have gone missing. I see the impacts on our salmon stocks from the mining activity. It was a harsh reality that I witnessed. I think that drives my work forward.

Obviously the climate crisis is not something that can be stopped, but we should do everything we can to reduce suffering.

I take seriously the call to step back so others can step forward, so that we’re not burning ourselves out. Me burning out would not be helpful to anyone. So I look after myself, and we look after each other. That brings me the most joy.

I see myself as part of nature, and nature is so resilient. Obviously the climate crisis is not something that can be stopped, but we should do everything we can to reduce suffering. I’m confident that no matter what, life in some form will continue. My responsibility is to preserve as much of that as possible.

Right now I’m really focused on redefining what sustainability means and critiquing white environmentalism and the lack of diversity in our climate movement so far, and helping people see their stake in anti-racism and in Indigenous sovereignty. And my call is just for others to pick up that work as well, and for settlers to have conversations about what our movement has lacked thus far and how they can be better allies.

We need to give youth space to do this work without passing off an entire weight.

We need to give youth space to do this work without passing off an entire weight. Recognizing that youth are so critical to pursuing climate action, but that we all have responsibilities and should be working intergenerationally to fulfill them. At the end of the day, knowing that I did my best — that I took up that responsibility — is enough for me to feel hopeful and sound in my work. And also, to look back at everything my ancestors went through. I’m sure at times it felt like the end of the world for them, but they kept going. And now I’m here, and I don’t take that for granted.

My name is Emmanuela Shinta. I’m a Dayak, the first people of Borneo. I belong to the Dayak Ma'anyan tribe. I live in Central Kalimantan, in the part of Borneo that belongs to Indonesia. Borneo is the third-largest island in the world, and is divided among Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei. My island has a lot of biodiversity — it’s one of the most ancient rainforests in the world, more than 140 million years old. It has a very rich and very beautiful landscape.

My people are the first people of the land, so we manage the land as Indigenous people do. For the Dayak, we live deep in the forest. It’s more than a resource or a commodity, it’s part of our daily lives. I always say to young people: you were born in Kalimantan as a Dayak, that’s not by accident. We have purpose as the first people of the land.

In 2016, we started this Ranu Welum Foundation. Our organization is defined as an Indigenous initiative. We combine Indigenous wisdom and modern technology to protect the forest, preserve the culture, and to fight for Indigenous rights. This activism isn’t just common activism — it’s Indigenous activism. That makes the burden two times heavier. And because you are a woman, and young, it’s three times harder. I’m depressed a lot.

What keeps me going is [knowing] that this is why I was born here. That is part of my purpose. If I don’t feel that, or take this role, then who? Then my life will be in vain. What’s the point of getting higher education or more money or a secure job, if your brothers and sisters are dying? For me, it’s very simple.

We know Indigenous people are less than 5% of the world’s population, but they manage more than 80% of the global biodiversity.

It hit me hard when I went to the villages and spoke with the elders and Indigenous leaders there. I saw with my own eyes the suffering, I heard by my own ears what they said. They said, we don’t want anything. We just don’t want what’s left to be taken. Don’t destroy anymore. Because it’s almost impossible for us to connect with our ancestors and our culture if the rainforest is gone. It’s like a part of yourself is gone.

So many people want to protect this planet together. And I want to get them to walk together. We can do this — Indigenous and non-Indigenous, men and women, young and old. No one can fight alone.

Indigenous communities are at the front line of environmental battles. We know Indigenous people are less than 5% of the world’s population, but they manage more than 80% of the global biodiversity. So if you talk about climate actions, climate justice, you should involve Indigenous communities.

I want people to understand that Indigenous communities are not the object of the green project. Globally, there are so many green movements. That’s good, that there are so many people who want to protect the world. But don’t come in and say hey, do this to protect your land! We know better how to manage the land. We have to decolonize climate justice. If you want to save the planet, reach out. You can’t just Google, you have to reach out to Indigenous communities and learn!

There is a lot of narrative, still, that’s in the colonizing language. It’s really, though, the fight of Indigenous communities. I want people to know there are people, brave people, who fight on the ground to protect our rainforest, to protect our planet. If you want to help, reach out to them. You will find out how you can support, how you can take action, how you can take part in saving this planet together.

My traditional name is Komangaapik. My English name is Ashley Cummings. I’m from Pangnirtung, Nunavut, but I’m currently living in Whitehorse. I’m attending Yukon University for a Bachelor of Indigenous Governance. I’m fortunate that I’m a good storyteller and people trust my words, so I’ve been doing speaking engagements for a few years now. My parents were always very big on making sure I knew my responsibilities as a human in this world. I also grew up around my grandparents, who instilled a lot of responsibility in me. I really grew into that, and as I got older and realized the injustices that Indigenous people were facing in particular, I felt a responsibility to share with the people who didn’t know about these things.

I grew up mostly in Nunavut, but when I was 12, I moved to Nova Scotia and realized a lot of people don’t know about the issues Indigenous people face. So I guess my activism started with me telling my friends and parents how different it is up north. And you can only talk about the struggles for long, so then I started focusing on the question, how can we change?

I really want to challenge folks to be their best selves, the ones they present on social media. If you’re going to support Indigneous people online, then help land defenders, volunteer with them.

The work itself can be so tiring. Really thinking about how often I repeat the same things, that exhausts me. But I do the work with and for other people — whether that’s my community, or for my two nieces and nephew who I love so dearly. That brings me the most joy. Because at the end of the day, you can only do your best, and my best is all for them. It’s all for the future generations. When I speak to middle school and high school students through the Connected North program, they’re always so jazzed to hear about the things they can do with their life and how the world is their oyster. They get so fired up. They want to help their communities in so many different ways, and that’s the most inspiring thing.

It’s great to promote anti-racism on Instagram or Facebook, but if you’re witnessing a person of colour or Indigenous person being persecuted for protecting their land, I really want to challenge folks to be their best selves, the ones they present on social media. If you’re going to support Indigenous people online, then help land defenders, volunteer with them. Support them monetarily, or if you can’t give that, talking is the best thing to do. Share the truth. If we can’t give money or time, we can give with our words.

My name is Na’ni’eezh Peter. I’m Navajo, Neetsaii Gwich'in and Ashkenazi Jewish. My people are from Arctic Village, but right now I live in Fairbanks, Alaska. I’m 17 and I just started my first year of college. Both my parents have been in this work for a long time. My mom helped co-found Native Movement, a grassroots organization that uplifts Indigenous voices and gives voice to the land. But it’s so weird when people say you’re an activist. It just feels funny to me, as an Indigenous girl in America. Because maybe I was just born an activist?

My people have gone through so much hardship. There’s been so much heartbreak, and devastation of the land. A lot of colonialism was about trying to erase our existence. So the fact that I’m even here serves as an act of resistance, it makes me an activist in that way.

But it’s so weird when people say you’re an activist. It just feels funny to me, as an Indigenous girl in America. Because maybe I was just born an activist?

I don’t think I was drawn to protect [Mother Earth]; I think it’s always been in my blood and spirit since I was born, as a part of my nature. That’s just who I am as an Indigenous person. And my love for the land: the Arctic, and the Navajo Nation — the mesa, the desert. And the border towns of Mexico and Arizona and New Mexico. I just want to protect that, for future generations.

What keeps me joyous and motivated is just being out on the land, learning from my elders. But it can also hurt, because I don’t know if the next time I’m back there, the plants will have died because of oil spills. And I don't know if Glacier Creek will still be the purest water I've ever had. Being out on the land fuels my love for it, but it also makes the heartbreak that much worse. Having self-confidence, and being connected, and being able to find inspiration in yourself is the key to winning the fight against climate change and all these corporations that will try to tear you down.

I’m White Mountain Apache and Navajo. I’m 19 years old and go to school at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. I am studying for a bachelor's in creative writing and Indigenous studies. It wasn’t until I won Poet Laureate [I started] to really think about activism and what it means to do that. I thought of activism as land defenders going to marches, or like my godparents going to fight the Dakota Access Pipeline. But as I got to learn about poetry and meet different poets, I realized activism can look like a lot of different things. I’m the oldest of five children. A lot of my strength and comfort comes from my siblings, because they also know about what’s going on in the world, but they still try to find good things in it.

I have a lot of faith in everyone who is a part of this movement, because we’re working so hard. We have the odds against us, but I believe that in the end we’ll be successful.

One of the more simple things people can do is try to figure out whose lands they are on. It’s a very big thing, to give respect to the people whose lands you are on. That’s a good way to get started, to take that first step. And sharing things you see on social media, like supporting Native artists or posting beadwork to your page. They seem like little things, but it can be overwhelming to just show up at a big protest or event. Those can be really emotional, and you don’t want to wreck the vibe. So start with small things and work your way up.

I’m incredibly hopeful about the future. I’m an optimist. I have such huge respect for our Indigenous land defenders, and I have a lot of trust in our creator that everything will be alright. I know that sounds so cliche. But I have a lot of faith in everyone who is a part of this movement, because we’re working so hard. We have the odds against us, but I believe that in the end we’ll be successful.

I would say the future is going to look pink and orange and yellow. Because those are the colors of good things and good feelings. In White River, my hometown, when I’m with my grandparents and we’re eating and laughing together, and we look out at the sunset, those are the colors of the sky. That’s what I hope the future looks like.

Michelle is a writer, editor, and magazine publisher. Her words have appeared in the Vancouver Sun, SAD Mag, Chatelaine, Vancouver Magazine, MONTECRISTO, and other publications. She lives with her husband, daughter, and weird cat in Vancouver, Canada.

This article was originally published on