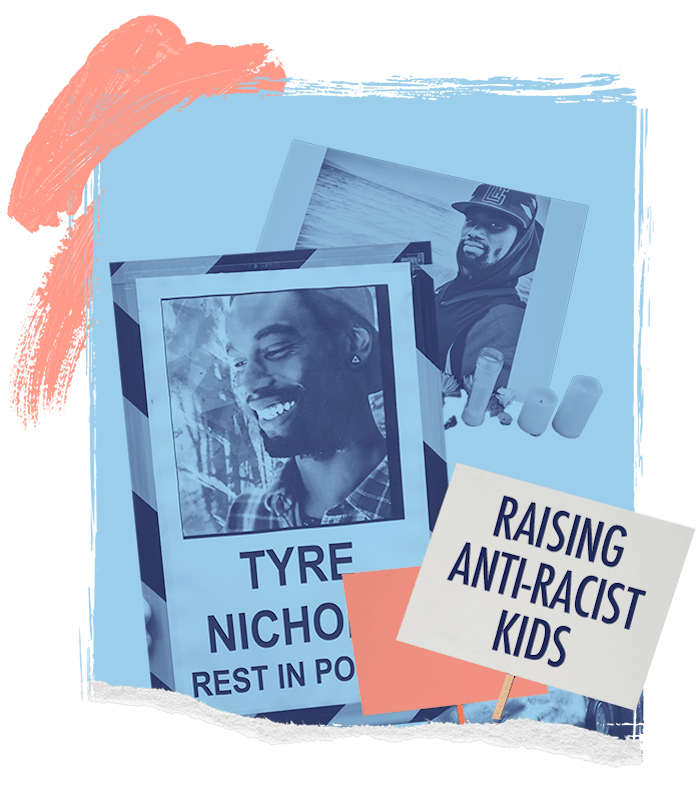

Raising Anti-Racist Kids

How To Talk To Kids About Tyre Nichols & Racist Systems

It’s urgent and vital that we take the conversation away from “good cops vs. bad cops.”

“Mom, could what happened to Tyre Nichols happen to you?”

My 8-year-old son asked me that this weekend, after my partner Adam and I took him and our 3-year-old daughter to a small protest demanding justice for yet another Black life slain by police. I struggled for words to address his fear. I finally explained that all the work we do to fight for justice — like marching — “is so that none of us have to deal with police brutality.”

Adam and I involve our kids in our advocacy — like going to protests — because it’s important for him to know that fighting for justice includes taking action with the community. Our daughter, at 3, is still pretty young so taking her to the action modeled to her what solidarity can look like. But the conversations we’ve had with our kids — and will continue to have — are as crucial as the actions we take.

Also over the weekend, I saw a message from a nearby police department stating that they “denounce the tragic death of Tyre Nichols in Memphis at the hands of the Memphis Police Department.” As I read this, I felt a familiar pang of frustration and anger at the failure of so many to grasp a fundamental reason why police brutality in this country continues to be a prevalent problem. The officers who allegedly killed Nichols may have come from the Memphis Police Department — and they may have been Black — but what really killed him and so many other Black people is the racist system of policing that remains funded and upheld nationally.

Police brutality is even more of an epidemic in this country than we think. In 2022, U.S. police killed 1,176 people, about 100 people a month. This was the deadliest year on record for police violence. Even as we make up only 13% of the population, 24% of those killed were Black people. Think of how many of those lives we did not hear about in the news. I am reminded that so many people who are responsible for our “safety” do not understand that police brutality towards the Black community is not a localized, sporadic issue, but a systemic problem that is birthed from the deeply racist history of policing.

But explaining all of this to kids can often be difficult — even the concept of a “system” is complicated. When I spoke to my son about the hope that drives our family’s activism, and tried to ease his anxiety about my safety, I could see the wheels turning in his head as he processed it within his 8-year-old perspective of justice. He seemed reassured in the moment, but I know this is a conversation that will be ongoing.

For every parent, it’s urgent and vital that we take the conversation away from “good cops vs. bad cops” and focus on the fact that the system itself is built on racist practices.

How to talk to children about all of this

So how do parents actually talk to our kids about racist systems? How do we explain it to them in a manner that they can understand?

Step 1: Explain what a “system” is using a community map.

Print out or draw this diagram, get the markers and crayons out with your kids, and fill it in with them:

Conversation starters:

- “Understanding systems is really hard but let’s see if we can find a way to understand it. Let’s make a community map to see who is in our community and which systems we take part in. Who are the folks in our inner circle? What about the medium circle who we see less frequently? What about the large circle who we’re not as close to?

- One way to understand systems is that it’s kind of like your body, with different parts, like arms, legs, hands, and ears. Parts of your body do different things but together, they keep you functioning. That’s kind of like how a system works. People and rules and practices and resources make up a system and together, they make it work the way it does.”

Step 2: Talk about how racism can be a part of systems.

Find ways to make it applicable to their life. For example, on your way to school, you can ask them what systems they see at school. These can be education systems, sports systems, even legal systems, etc.

- “Racism is when people are treated unfairly because of the color of their skin, the shape of their eyes, where they are from, the texture of their hair, and other factors. Racism can happen between two people, and it can also happen when groups of people set up unfair rules for others because of some of the factors we just talked about. Let’s look at our community map. Racism can happen here (point to places on the map) in systems. A system can be everything from a school or a hospital to a police department.

- What systems do you see in our community?

- Fighting racism can be hard, but we need to make sure that we’re all doing what we can to stop it.

- What does fighting racism look like for you?

- What do you think we can do to fight racism in some of these systems?”

Step 3: Talk about the history of racist policing.

- “Racism exists in policing because some of the roots of policing were to stop people who were enslaved from being free and to return them to the people who were enslaving them.

- This was done through violence.

- We can see some of that violence in how police deal with Black and Brown people today.”

Try to keep your sentences short and pause to check in with them on any thoughts they’re having. This conversation also won’t be done in one day. Keep coming back to it over and over again, taking breaks as needed. And instead of focusing on the fears that come with racist systems, focus on the opportunities that we can all have when we make change together. As your kids get older, their understanding of racist systems will shift and you’ll need to revisit things again and again to address their growing curiosity.

The important thing to remember when talking to your kids about racist systems is that it’s OK to not have all the answers. It’s OK to pause and reflect humility by letting them know you don’t know the answer and will come back to them when you do some more research. Educate yourself so that you can share this knowledge with your kids.

As we mourn Tyre Nichols, Carl Dorsey, and so many others who have been killed by police, families can teach our kids that our role in systems is to ensure it is working for everyone. If it’s not, then we shouldn’t be afraid of doing the hard work of imagining and birthing ones that do.

Further action steps for parents

- Learn about the racist roots of policing baked into its DNA.

The NAACP traces some of the origins of modern-day policing to slave patrols that were formed in the early 1700s with a purpose “to establish a system of terror and squash slave uprisings with the capacity to pursue, apprehend, and return runaway slaves to their owners.” These slave patrols lasted well until the Civil War.

When parents understand that the origins of policing laid the foundation for police brutality against Black and brown people, we can better explain to our kids that this system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as intended. It’s a product of white supremacy culture, one that the National Education Association describes as “a political ideology and systemic oppression that perpetuates and maintains the social, political, historical and/or industrial white domination.” White supremacy is an ideology and a belief system so it can be upheld by people of any race, hence the reason a police officer’s race has nothing to do with their likelihood to commit police violence.

- Research how we can fund community solutions instead of racist systems.

When the defund the police movement gained national prominence, many balked at the idea of removing police from communities. But one crucial point is missing in this understanding. Defunding the police means taking funding away from the racist system of policing and investing it in community-based solutions — ones that keep all of us safe.

One example of an alternative-to-policing solution that seems to be working right now is the Portland Street Response, a local initiative that provides “a first-response alternative to police or other emergency services” specifically to people who are experiencing non-life-threatening mental and behavioral health issues. The program’s success extends beyond just existing as an alternative to calling 911 (which can turn lethal for those with mental illness) — helping people secure housing and food.

Raising Anti-Racist Kids is a monthly column written by Tabitha St. Bernard-Jacobs focused on education and actionable steps for parents who are committed to raising anti-racist children and cultivating homes rooted in liberation for Black people. To reach Tabitha, email hello@romper.com or follow her on Instagram.

This article was originally published on