A Birth Story

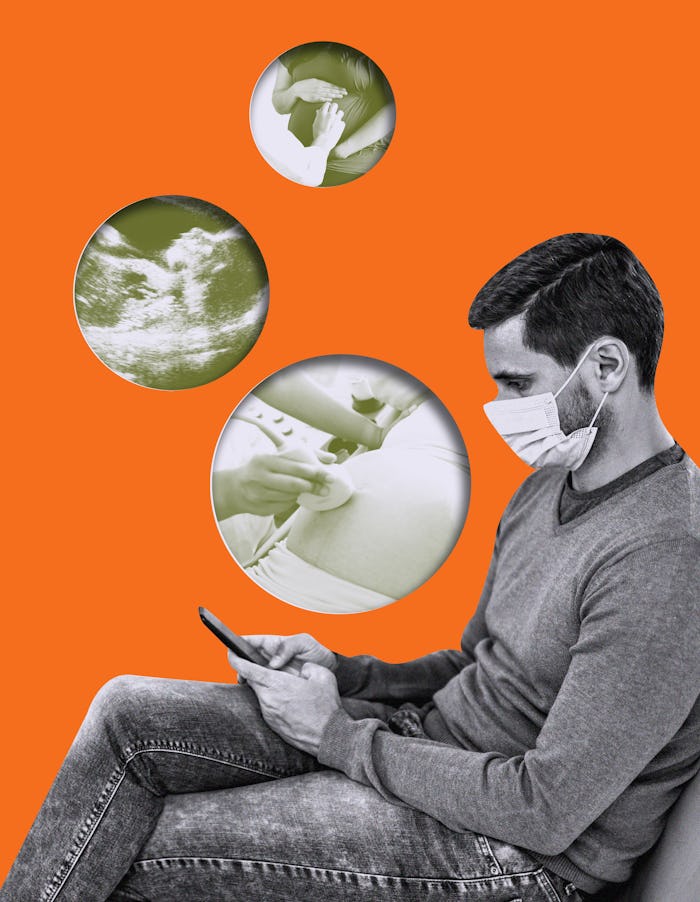

Fear And Missing Out: I Became A Dad During COVID

Throughout my wife’s first pregnancy, the pandemic kept me out of the doctor’s office — even when things got really scary.

When the world was two months into a pandemic, I was laid off from my job and found out I was going to be a father.

A few weeks later, in June 2020, I drove her to her first doctor’s appointment and sat in the car for an hour, reading a book, trying to distract myself. We had been trying since we got married in 2018, and after 18 long months, the fear of a false positive was profound. When I drove her again the next visit, I asked whether I could go inside — even if it meant sitting in the waiting room. Not with the pandemic raging, they said.

I still drove her to every appointment, sitting alone sometimes for hours with only my own thoughts. I had a constant fear that every appointment would bring bad news, that a miscarriage was not only possible but inevitable.

By a visit around the 14-week mark, my anxiety was palpable. Palms were sweaty. My thoughts raced without abandon. I kept thinking that if our fears were realized, she would be alone to consume the terrible news. Then, she would have to tell me afterwards.

But when I heard a smack on the passenger side, her smile was as wide as I had ever seen, pressing the ultrasound photo against the window. We both cried. A part of me cried extra because I didn’t get to see the baby.

After every appointment, my wife would relay details to me in rapid-fire mode — about our son’s growth patterns, his huge feet, how he relentlessly touched his face — and I felt like I was missing out.

It wasn’t a depression I developed, but more of a general malaise. After every appointment, she relayed details to me in rapid-fire mode — about our son’s growth patterns, his huge feet, how he relentlessly touched his face, and I felt like I was missing out.

Then, halfway through her pregnancy, she and my in-laws surprised me. There was a medical practice an hour away allowing couples to experience ultrasounds together. When we pulled into the parking lot that weekday afternoon, a couple had just exited the building with elation, holding photos and kissing. But emotions swiftly changed once we entered the building and saw a young couple in tears. Kelsey and I heard an employee explain that the fetus doesn’t always want to show face.

But our son bared all. It was worth the wait.

Kelsey entered labor four days before her due date. She woke at 5 a.m. and knew it was time. We threw our packed belongings in the car. I stopped and bought her favorite bagel on the way.

Shortly after she received her epidural, her doctor arrived. It was the first time I met her the entire pregnancy.

She was calm, almost stoic. Her vitals were great. Due to COVID, everything I knew about labor was from Zoom classes or books. There was no in-person CPR class. No Lamaze. My mind raced, wondering what was going to happen. Is Kelsey going to be OK? What am I supposed to do during the labor? I won’t be comfortable until the baby is out and breathing fine.

Shortly after she received her epidural, her doctor arrived. It was the first time I met her the entire pregnancy. Along with a delivery nurse, their gloves went on. The doctor told me to stand beside Kelsey and hold her left leg while she pushed. This is really happening, I thought. No pomp and circumstance.

One strong push occurred, followed by encouragement. This is happening too easily. On push No. 2, all hell broke loose. Looks of consternation echoed across the room. The nurse rushed to the monitor to check on the baby.

Kelsey swung her head 180 degrees, from the monitor then to me. “What’s happening?” she yelled. I was frozen, torn between wondering if the worst thing that ever could happen just did and holding her hand, telling her everything was OK. Within seconds the door slammed open and myriad nurses entered. They ripped cords out of outlets and rolled my wife out into the dead hallway. I chased down Kelsey, who was visibly panicking. I asked one nurse what the hell was happening.

You know those moments in life where it feels like you’re living an out-of-body experience, like you’re watching the scene play out and have little to no control over the final product? That was what it felt like, but worse. The nurses crowded around her, pushing her into the emergency room to conduct an impromptu C-section. I yelled, “Kels, I love you!”

She later said she never heard me.

I was forced to wait outside the room, where I was instructed to put on a surgical gown. I held my face in my hands, my foot nervously tapping the floor with reckless abandon. While a nurse tried to talk me off the proverbial ledge, intrusive thoughts filled my head: Our child could be gone forever, before we even meet him. All the weeks and months of planning and anticipation would end in the worst agony of our lives.

Then, the reality of Kelsey’s condition became too real. Even though she was the biggest fighter I had ever known, some moments are bigger than any of us and out of our control. My mind was spinning rapidly into panic mode, wondering if the baby had died and Kelsey had survived, or vice versa. Or maybe they were both victims of unspeakable trauma, I thought, and it would be just me walking out of the hospital, alone. At this juncture, while being punched across the face with the reality that I could lose my wife and child, the fact that I wasn’t in the delivery room meant less to me than having everyone come out of this unscathed. All I wanted was a confirmation of their conditions, but nobody told me anything.

You know those moments in life where it feels like you’re living an out-of-body experience, like you’re watching the scene play out and have little to no control over the final product? That was what it felt like, but worse.

In such instances, it’s difficult to be either optimistic or pessimistic. Time stops. All you have is some semblance of hope in the pit of your stomach, the gut feeling you have trusted your entire life, that everything will be OK.

Meanwhile, I could hear Kelsey screaming in agony — a sound that to this day and for the rest of my life will haunt me. I later discovered they cut her open without providing anesthesia. There was no time: It was seven minutes between the first vaginal push and the removal of our child.

Once I received the green light to finally go inside, I rushed through the doors and saw the immediate juxtaposition: Kelsey’s head was on the left side, a blue cloth partition at her neck; on the right were a handful of doctors covered in copious amounts of blood, pushing her insides back in and sewing her up.

“Where is he?” she shouted, referring to our new son, River. “Is he alive?”

I had no idea myself. My first instinct was to tend to my wife. I sat down on a chair pulled up beside Kelsey’s head, grabbing her hand as tight as possible while looking around the room for our child. I overheard a nurse mention something about his lungs.

Then suddenly, we heard crying. A nurse snuck up behind me and introduced River. He was 8 pounds, 8 ounces, with normal vitals. He came out with a head full of hair. I held him and cried while Kelsey stared, mentally and physically drained.

After she was sewn up, I laid River in the bed with her, provoking more tears. As if River knew her pain, he instantly grabbed her finger.

He is a constant reminder of the fragility of existence, that what is here one day may not be the next. When he cries, I feel grateful that he has that capability to live and breathe and be a human. When he laughs, it reminds me of all we could have lost.

River turned 4 months old in mid-June. He is very healthy, always giggling. He shares personality traits from his mom and dad. People often say he’s a miniature version of myself: relaxed and inquisitive, possessing a particular grin.

I knew he would consume all my love, but even I am not fully aware how his birth impacted the way I look at him. He is a constant reminder of the fragility of existence, that what is here one day may not be the next. When he cries, I feel grateful that he has that capability to live and breathe and be a human. When he laughs, it reminds me of all we could have lost.

Kelsey and I sometimes go back and discuss what happened. We wonder whether River somehow, now that he’s older, has some innate knowledge of what occurred. We imagine that he understands, intuitively, what led to his life as he now knows it.

The entire experience initiated a newfound appreciation for my wife, and I believe she too for me, for the lengths you will go for those you love most. Juxtaposed with his birth, everything I missed out on due to the pandemic becomes less important.

I have come to terms that it was not permanent, that while I missed out on certain aspects they weren’t the moments that mattered most in the long run. Rather than dwell on the past, I find it more vital to live in the moment and not waste any time I have with my son.