PICTURE DAY

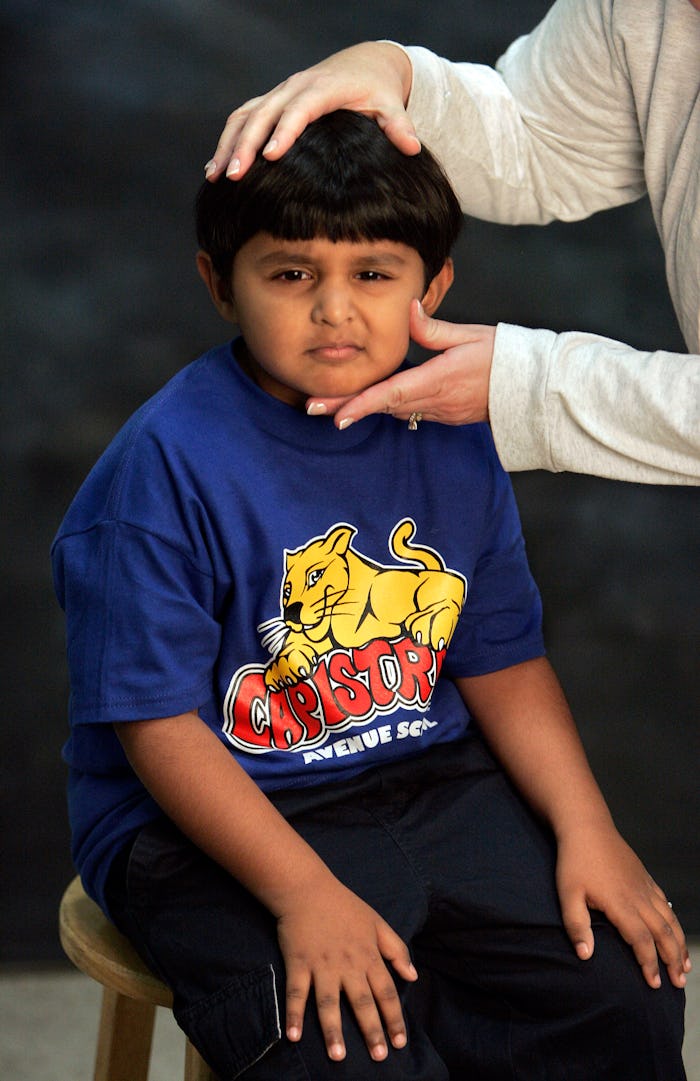

Please Tell Me No One Is Actually Paying To Retouch Their Kid’s School Pictures

I want to remember my kids exactly as they are at this stage of life.

This fall, my four kids returned to in-person school after 18 months. I was so excited for the return of school picture season. As I filled out the familiar Lifetouch order form, I noticed a new section at the bottom that made me queasy. Did I want to, for $17, retouch my kids’ photos? They could whiten their teeth or “smooth” their skin. They could even remove blemishes or scars — if we ponied up.

I thought of the shoebox that sits on the top shelf of my mom’s closet and holds a collection of our school photos from the ’80s and ’90s. They are terrible — big bangs, curly mullets, too many neon patterns used in conjunction. My brothers and I have missing teeth and scrapes on our faces from biking mishaps. But our childhood is preserved in those faded wallet-sized photos, and we laugh every time we go through that box, remembering how terribly awkward childhood is.

Plus, we all had to suffer through terrible school photos, and our kids should have to, also. When I ranted about how uncomfortable this new option made me, my friend Rob shared his school photo from the year he fell out of bed the night before. Those are the memories we want to preserve, I thought, not some Instagrammable filtered shot.

And what message does that send our kids — that zits and missing teeth aren’t a completely normal part of life, but something to be embarrassed about?

Given the recent concerns over how Instagram is affecting kids’ mental health and body image, do we really want to take the culture of Instagram filters and apply it to school photos, too? And what message does that send our kids — that zits and missing teeth aren’t a completely normal part of life, but something to be embarrassed about?

Leah Jacobs lives with her partner, Victor, and two kids, ages 5 and 10 months, in Pittsburgh. She has significant facial scarring from childhood cancer treatment and surgery. It took her a long time to love herself, she told me. If retouching had been an option, she said she would have clamored to use it but that “it would have reinforced the messages I had already received elsewhere that there are good ways to look and bad ways to look, and that if I didn’t align with the good ways, then I should pay to have that remediated.”

I wondered about how photographers decide what exactly to retouch, especially when it comes to kids, who might not even be able to consent to changing their appearance. Christine Han is a food, portrait, and lifestyle photographer based in New York City who works on commercial shoots and often takes retouching direction from an art team.

When she is working with portraits, though, she does minimal retouching. “People look beautiful as their natural selves, and I do my best to shoot the subjects in flattering light, which goes a long way,” she says. She does very basic editing for color and tone, but not much beyond that for kids. “I don’t think we should make it a habit to retouch photos of young kids. I’m afraid the message to them would be that they are not OK as they are, and that is just untrue. Life is not about image, and we have enough of that pressure going around without retouching little kids!”

I want to take their perfectly imperfect images and hang them front and center in our entryway, letting them know that I love them wholly exactly as they are.

Jamie Davis Smith is a Washington, D.C. photographer who focuses on family photos, and she echoes Han’s methods as well as her concerns. “I always try to capture families as themselves, even if that is sometimes imperfect,” she says. “I try to capture what families feel for one another rather than focusing on what they look like.” She will correct for bad lighting by brightening a photo or removing shadows off a face, but she works diligently to not alter the appearance beyond that.

The message that our natural state is not acceptable is pervasive, though, and Smith tells me she gets more requests from adult women to alter photos than from any other group. “They want to appear thinner and to have smoother skin,” she explains. “Society sends a lot of messages to us as we grow that we should change our appearance in various ways. As a photographer, I don’t want to contribute to the development of these issues.”

Of course, as a mother, I don’t want to contribute to them, either. I didn’t check that box on my kids’ forms. Not only do I not want to spend another $68 on already-overpriced shots, I want to remember them exactly as they are at this stage of life. They just survived a terribly traumatic global event. They were resilient, strong, and brave as our family navigated everything the pandemic threw at us. Maybe we got a bit lazy with our morning routines. Maybe my youngest’s at-home pandemic bangs are not quite even, and one of my twins has a scar on her forehead from a scooter tumble. I want to take their perfectly imperfect images and hang them front and center in our entryway, letting them know that I love them wholly exactly as they are.

This article was originally published on