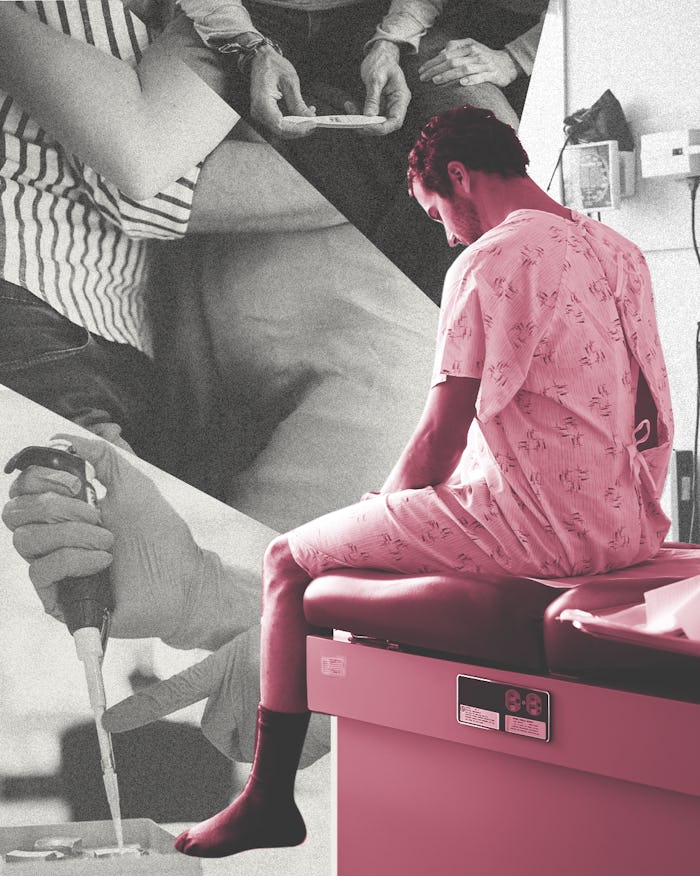

Trying To Conceive

My Wife Let Everyone Assume She Was The One Dealing With Infertility

I was the reason we couldn’t get pregnant — and I couldn’t talk about it with anyone.

My journey to fatherhood began with laughter. To be more specific, a doctor was laughing at my balls. Well, he wasn’t laughing at them, per se. He was laughing at the obvious discrepancy in their size. Obvious to him, at least. As a testicle layman, I couldn’t see it — they looked the same to me. I mean, I’ve had these balls my entire life. I thought I knew them intimately. I guess not.

Nevertheless, there I stood, pants at my ankles, as a vaunted urologist chuckled at my testes. He told me without hesitation that if my wife and I wanted to have a baby, I would have to undergo a varicocelectomy, a procedure to help the blood flow properly to that clearly undersized testicle. If I underwent this procedure, he assured me that we would “have no problem getting pregnant.” And, as a bonus, my smaller ball would finally stand eye-to-eye with his big brother. Then the doctor stuck his finger up my butt, asked me to cough, and told me to go take care of my co-payment.

I’ll understand if you want to click away from this story. Not many people enjoy talking about men’s balls, and it seems even fewer people like talking about male infertility. I’m not even sure I want to discuss it, but I feel that I have to. There’s a dearth of conversation surrounding male fertility issues. Confronting my own fertility challenges prepared me for being a father in ways I couldn’t have imagined and not only pulled me into a deeper partnership with my wife but profoundly changed the way I think about masculinity.

“Trying” is code for “doing it!” Oooh. But the sexiness was draining from the sex.

My wife, Meredith, and I “pulled the goalie” a few months before we got married. No more birth control, no more safety net, just carefree let’s-see-what-happens sex. We knew we wanted kids and were both in our mid-30s and well aware of that dreaded ticking clock. According to ReproductiveFacts.org, fertility in women “gradually declines in the 30s, particularly after age 35. Each month that she tries, a healthy, fertile 30-year-old woman has a 20% chance of getting pregnant.” And it gets even more difficult to conceive as women approach 40. If we wanted a family, we figured we’d better get started ASAP. It didn’t even occur to us to worry about my age at this point. After all, men can have babies well into their dotage. Robert DeNiro was a new dad at 68! Charlie Chaplin at 73! I was only 36. And I love those actors! Not going to be a problem.

When people asked us whether or not we had kids, we answered “No… but we’re trying.” The asker of the question would then titter with naughty excitement. “Trying” is code for “doing it!” Oooh. But the sexiness was draining from the sex. Stress began to mount as logistics entered our bedroom. Ovulation charts were being dutifully followed. Temperatures were being taken. Sex was happening at odd, nonsexy hours. During one particular attempt, I think we were watching Game of Thrones and didn’t press pause.

After a year and a half of “trying,” we knew we had to get more serious. We both decided to get examined by specialists. After examining her ovarian follicles, Meredith’s OB-GYN told her she was “as fertile as an 18-year-old.” All indicators pointed to her body not being the issue. So then the problem was mostly likely… me. But I’m like Robert DeNiro and Charlie Chaplin, right? It was time to find out.

What made my semen analysis unforgettable was the poster of a nude Anna Nicole Smith hanging prominently on the wall of the room in which I was to “extract my sample.” This wasn’t a subtle, magazine-sized photo of Anna Nicole. It was a nearly 5-foot-tall framed print. Her life-sized eyes gazed directly into mine as she wrapped herself around a very muscular and equally naked man whom I did not recognize. “Isn’t she dead?” I asked the sperm-sample collector man. “For, like, a long time now?”

He shrugged and answered a question I hadn’t asked. “When you’re done, take it down the hall to the right.” He handed me a small plastic cup and gestured to a TV on a stand in the corner. “There’s Roku on the TV with lots of options. And magazines if you want.” I nodded a tacit thanks as he closed the door behind him.

The results of the semen analysis were dismal. “Low sperm concentration with low motility and abnormal morphology.” I had won the triple crown of male infertility: A paltry number of sperm cells that didn’t swim well and looked wrong. My semen would most likely fail to get the lower-than-ideal number of sperm all the way to my wife’s egg, and even if they did manage to get there, the cells would have a hard time delivering my genetic material because of their wonky shape. It was official: I had male fertility issues.

The last time I failed a test so spectacularly was a calculus quiz in my junior year of high school. There were three questions. I got only one right. The other two questions looked so foreign to me that instead of using the space provided to “show my work,” I filled the paper with some jokes I thought the teacher would enjoy. He did, but I still failed the test. The stakes of that calculus test were basically zero, though. How often do you use calculus if you don’t work at the Jet Propulsion Labs? On the other hand, how often do you use semen? I had been trying to use mine for 18 months with nothing to show for it.

At first, I laughed this failure off like I did the calculus test. I figured it wasn’t a test I could have studied for, anyway. While Meredith and I were “trying,” I did the bare minimum to try to help my sperm stay healthy. I stayed out of hot tubs and kept the laptop off my crotch and avoided wearing tight pants which, if you know me, is difficult because I’m kind of a tight pants guy. And yet, I still failed this test. But no big deal, right? Chandler Bing had bad motility.

I simply hadn’t even contemplated the possibility that I might be the infertile one.

Despite all the outward bravado, I was devastated. Why was I so surprised that my body was the reason we were struggling to conceive? For a million reasons — cultural, historical, religious, political, etc. — the discussion of fertility has been centered almost entirely around women. Perhaps that’s because women carry the vast majority of the physical burden of bringing a baby into the world. Moreover, those panic-inducing statistics about age and its correlation to declining female fertility have been repeated so many times, in so many articles, and as the de facto explanation for women’s baby-crazy behavior in countless movies and TV shows. But this female focus created a blind spot for me. I simply hadn’t even contemplated the possibility that I might be the infertile one.

Call it blissfully ignorant male privilege, but at that point in my life, I hadn’t seen anything in popular culture that had discussed male infertility with any kind of nuance or maturity. Chandler’s swimmers, after all, were ultimately upstaged by Monica’s inhospitable womb. Most of what I heard growing up were infantile pejoratives about impotent losers who “couldn’t keep it up” or were “shooting blanks.” I hadn’t realized how profoundly manhood and masculinity were tied to virility. Powerful men are assumed to be more virile and virile men are assumed to be powerful. A man without power is impotent, a “cuck.” This is a trope as old as time and despite knowing better, intellectually and morally, I realized with some shame that I did not want to be on the nonvirile side of it.

My balls would remain the same — as gross as ever.

That brings us back to where we started this story: the urologist’s office. After laughing at my balls, the urologist explained to me that if I got the varicocele procedure, my morphology and motility problems wouldn’t be an issue since there would be a lot more sperm. “If you have a sluggish army of 1 million, it’s better than a sluggish army of 1,000.” Of course he put it in terms of weapons and armies and masculine motifs. And it worked. Hey, I loved G.I. Joe as a kid. Let’s do this, soldier! I decided in that moment that even though I was “shooting blanks,” I was not powerless. I trust doctors, I’m not afraid of surgery, and I was devoted to making a family with Meredith. I decided instantly — as I pulled up my pants and marched out to the reception area to take care of that co-pay — that I was going to go under the knife. But I was not going to discuss it with anyone.

As our close friends and family became aware of our struggles, the common assumption was that Meredith’s body was the culprit. This is the assumption almost everyone makes when they hear that a straight couple approaching 40 is having a hard time conceiving. Many well-meaning friends offered Meredith unsolicited and highly inaccurate advice on maximizing her fertility or told her stories of other women in similar predicaments.

Meredith didn’t correct them, though. She was protecting me from talking about something that was clearly mortifying for me. Her silence was a new kind of romantic gesture I’d never experienced before, a kind of love I hadn’t known in my adult life. My wife was trying to shield me from shame. It didn’t seem fair to me that Meredith was the center of all the glare, and she wouldn’t have been if I hadn’t been harboring that undeniably deep embarrassment about my infertility. I wanted to shout that my body was the problem and that my wife was “as fertile as an 18-year-old,” as the doctor had put it. But I was terrified of opening up. If I wanted to shift the awkward body conversations from my wife to myself, I was going to have to step up and start talking.

As an actor, I’m mostly comfortable in my own skin. I don’t embarrass easily and I’m certainly not modest, but I quickly learned that discussing infertility required a different kind of courage than performing half naked with a clown nose on. When we shared the news about my impending surgery with some very close friends, the first response I heard was “Yuck!” A much younger female friend visibly winced in disgust. “Are you going to have, like, Frankenstein balls?”

I quietly explained that, no, the incision would be near my belly button, but to the left and down a smidge. My balls would remain the same — as gross as ever. Everyone laughed as we do when we’re coping with awkwardness and discomfort. Our friend sweetly backpedaled, explaining that all surgeries gross her out. I rolled with the jabs, adding a few self-deprecating riffs about my “ball surgery.” Hey, it’s my job to entertain. Balls are funny!

Inside, though, I was suffering. I was beginning to spiral into a strange new era of body self-consciousness, bordering on self-loathing. I’ve had some body issues before. I was that lanky kid who couldn’t gain weight no matter how much I ate, so I used to dread summertime pool parties and I avoided playing basketball games where the teams were “shirts versus skins.” Most of that self-consciousness faded away with time. As an actor, I’ve had wardrobe fitting where I stand like a mannequin in different outfits before a group of producers, directors, and assorted crew members, so I’ve heard plenty of negative feedback about my body. But I’ve also had lovely feedback, beautiful things that have been uttered to me in intimate moments. I’ve internalized both the good and the bad. The “ball surgery” jokes felt different somehow, more intense and far more unsettling. It felt like my core identity was being scrutinized, as if my value as a man was being attacked. I realized this is what women feel like all the time when they deal with infertility, but I also know that they talk about it with each other, support each other. Men… don’t. I certainly didn’t want to.

The unknown can be scary, but it can be thrilling if you’re partnered with someone who can sometimes take the reins and be the brave one.

I put my head down and quietly dealt with this stew of shame alone. I pretended that the jokes about my “Frankenstein balls” were funny and that having surgery was “no big deal.” This denial took a huge toll on me. I had worse self-esteem than when I was that concave 15-year-old.

Luckily, Meredith noticed that I was withdrawing into a somber depression. After a little cajoling, I finally admitted to her that all the jokes about my “ball surgery” were affecting me in a totally unexpected way. I was afraid that if I said anything about it, I’d appear touchy and oversensitive which, of course, is a no-no for men. But if I didn’t talk about my feelings, I would sink even further. She smiled and held my hand. The simple act of acknowledging my discomfort instantly eased the loneliness. The unknown can be scary, but it can be thrilling if you’re partnered with someone who can sometimes take the reins and be the brave one.

Meredith was now that person for me. In this moment of vulnerability, she was holding me up and feeding me courage. At the same time, she knew that despite what I was going through psychologically, there was no question that I was going to have the surgery for our family. She saw that I was unwavering and devoted. This was a deepening of our relationship that neither of us had truly anticipated. This was marriage 2.0. Although that whole stress-filled time of failed baby-making had taken on epic levels of unsexiness, this was maybe the most romantic moment of my life.

It was this deepened bond, this shared mission, this exchange of strength and support that put Meredith and I in lockstep as parents. We were galvanized as a unit for the sake of our potential child. As a parent, you have to make unexpected sacrifices and find untapped strength when you feel exhausted or depleted. This was our first step into that new territory.

It was also through this experience with infertility that I started to redefine my own masculinity. It takes a herculean effort to slough off a lifetime of programming, but that’s what I’m attempting to do, continuously, not only for the sake of my own happiness but, for my wife, our children, and even, potentially, for the sake of other guys out there who have struggled to open up about things that they were told never to open up about. We live in a time of strongmen and bullies who gave rise to the term “toxic masculinity.” But we also live in a time where accountability has started to dismantle their power. It can seem at times like the spectrum of manhood in America vacillates between two poles: Either you’re toxic or a you’re a snowflake. But, of course, that duality is a myth. We’re in a new era of fluidity that has given rise to glorious new possibilities of expression for men of all shapes, sizes, colors, and orientations.

For a lot of men, this new world feels like a threat, a time without rules or guardrails. To me, this dazzling display of diversity takes nothing away from what it is to a be a man. Instead, it offers us more freedom than we have ever known. And that freedom has the power to eradicate shame. Maybe a powerful man isn’t aggressive or even virile. Maybe he’s simply unafraid and ready to help you feel safe, regardless of your gender.

If we’re going to talk about parental equity, then we have to include every step of the process it takes to get there, starting with fertility.

The surgery was a success in that my balls are now (evidently) the same size. Unfortunately, the urologist’s prediction was otherwise wrong, and the surgery did nothing to address my fertility issues. A few months later, we decided to embark on the next step of the journey to parenthood: IVF. Our experience was harrowing and truly miraculous, involving mosaicism and genetic tests gone awry. It created an unprecedented level of stress in our lives, but it also produced an even deeper bond between me and Meredith. It’s quite a story — one for another time — but I will stop burying the lede and tell you that it resulted in the birth of our beautiful daughter, who is now back at school in person after a year at home with her mom and dad.

I often tell people that preparing to become a parent is like reading about music or training to be an astronaut. You can approximate the experience ahead of time, but nothing fully prepares you for the real thing. My head-on collision with infertility prepped me for what is now my life as a father. I felt — in my mind, in my heart and in my body — what it feels like to push through shame, depression, fear, and the resulting exhaustion for the sake of devotion and love. I faced a situation where I felt out of control, and as if my choices had narrowed to a few, unhappy options.

It felt a lot like parenting.

Andrew Burlinson is an actor and writer whose career spans over twenty years in theater, television and film. Best known as Scott Quinn on the Emmy nominated Amazon Prime original Just Add Magic and as Burly, the guitarist for Mouse Rat, on Parks and Recreation, Burlinson was a Blue Man in the world famous Blue Man Group, and has appeared in so many commercials that someone at a baseball game once recognized him as “that guy from that thing on TV.”

Originally from New York, Burlinson has a BA in English from Harvard and studied acting in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. He co-wrote the award winning new media series Grip and Electric, which was recommended by The New York Times and Tubefilter. He lives in L.A. where he spends a lot of time jamming in the garage and perfecting his killer chocolate cake recipe with his wife and daughter.

This article was originally published on